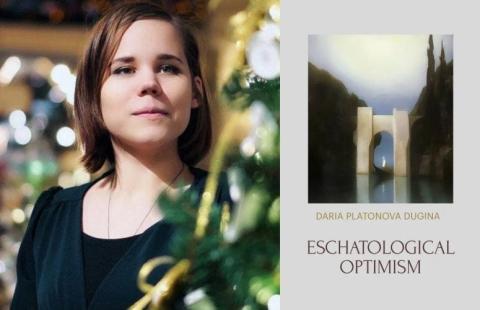

Daria Dugina's Eschatological Optimism

Primary tabs

Excerpt from the Foreword to Daria Platonova Dugina, Eschatological Optimism (PRAV Publishing, 2023).

The Moment of Sophia

It is very difficult for me to write about Daria, because, especially in recent times, she had become everything to me: a friend, a thinker, a joy to be cherished, a partner in dialogue, a source of inspiration, and a pillar of support. The pain from losing her doesn’t dare subside; on the contrary, all of it persistently flares up with ever renewed force. Nevertheless, I understand that it is necessary to open her book, Eschatological Optimism, with words that she herself would have liked to hear and which might be useful to the reader.

Daria Dugina was a thinker, a philosopher. She was such organically and wholeheartedly. Yes, she was at the very beginning of her philosophical path, and some thoughts and ideas require a long time, sometimes many years (and others many centuries), to be thought through, but that is another matter. Something fundamental is decided before all else: whether you are a philosopher or not. Daria was a philosopher. This means that, whatever her path through the worlds of philosophy could have been, the beginning of her path is already valuable, important, and deserving of attention. The most difficult thing of all is to get into the territory of philosophy, to find an entrance into the closed palace of the king. One can besiege its walls for as long as one likes, yet still remain outside of it. To break through and find oneself in this most securely guarded palace depends on the vocation, the Call, that the genuine thinker hears in their depths. Daria heard this call.

Aristotle distinguished between two kinds of systematic thinking involved in philosophy. The first is the moment of sophia (σοφία), the sudden and instantaneous flash of the mind, the illuminating insight of the Logos. Such a flash might occur in one’s youth, adulthood, or old age. It might not happen at all. According to legend, Heraclitus claimed that up to a certain moment he knew nothing, and then he knew everything all at once. This is the moment of sophia. For Heraclitus, as for Aristotle, the Logos is one and indivisible. If someone has been granted the honor of experiencing its presence, they henceforth become a different kind of human: a philosopher. Henceforth, whatever this person thinks, wherever they turn their gaze, they now act and live in the rays of the Logos, in communion with its unity. This is what happens when one is initiated into philosophy. In Plato’s Republic, this is called noesis (νόησις), the capacity to raise individual intellectual conclusions up to the primordial and supreme world of eternal ideas. Daria Dugina bore this mark. She passed through the moment of sophia, and it was irreversible.

Her Phronesis

There is yet another, second kind of thinking. Aristotle called it phronesis (φρόνησῐς), and Heraclitus pejoratively called it “polymathy,” that is “having much knowledge” (which, in his opinion, “does not teach the mind”). In Plato, this corresponds to dianoia (διάνοια), or that rational thinking which does not collect everything together into one, but divides everything into parts, classes, and categories. If sophia comes instantly (or never), then phronesis necessarily requires time, experience, study, reading, observation, exercise, and diligence. Phronesis is also important. The crux lies in this: if the experience of sophia has taken place, then further exercise of the mind is always built around the immutable axis of the Logos. If it has not, then phronesis becomes something like common, mundane wisdom, which is, of course, valuable, useful, and deserving of all sorts of praise, but has nothing to do with philosophy. No matter how much phronetic people may exercise reading, analysis, and rational operations, if they have not previously entered the closed palace of philosophy, then their activity — no matter how stubborn and intensive — remains like wandering around the outskirts. This might be technically useful, but it nonetheless remains something completely exterior and, in some sense, profane.

It is in this sense that Daria’s phronesis stood only at the very beginning of a great philosophical path. She was just beginning to master philosophy on the fundamental level, to deepen her knowledge of theories and systems, to become fully acquainted with the history of thought, theology, and the infinite field of culture.

Here, perhaps, is the most important point of this book, Eschatological Optimism. This is a book of living thought. What is important here is not the scale, depth, or sheer volume of the theories, names, and authors cited in it. What is important is how a genuine philosopher reveals, lives, and embodies what they think in their very being. What is important is that they think philosophically, in the light of Sophia. Herein lies the novelty and freshness of this book. In the end, Daria writes and speaks not in order to move outwards to meet diverging lines of interpretations and observations of details, but to invite those to whom it speaks to make their journey inward, to live philosophy, to commit to a “turn” (ἐπιστροφή), as the Neoplatonists called it, and which Daria reiterates by no coincidence. This turn is key to her. Having experienced Sophia, she wanted to help others — readers, listeners, all of us — to experience the same illuminating insight by the Logos. Her book consists of multifaceted and widely differing approaches to the closed court of the king — in one place there is an imperceptible breach in the wall, in another there is an underground passage, in another there is a low-lying fence. Whoever has been inside knows how to enter, how to exit, and how to return.

Therefore, Daria Dugina’s book is initiatic and dedicatory. For someone who has the gift, the calling, the will to philosophy, this book might become a revelation. For phronetic people, it might be a useful and concise encyclopedia of Platonism. For aesthetes, it might be a model of graceful thinking. For those seeking the mystery of Russia, this book might be a humble milestone along such a difficult and noble path.

Daria as a Sign

Daria Dugina’s book is also a sign. Martin Heidegger complained that people who are deaf to the true call of the Logos tend to take the sign, the icon, or something pointing to something else to be self-sufficient. In this lies philosophical idolatry. The meaning, significance, and predestined purpose of a sign is that it points not to itself, but towards something else. Its appeal is such: look not at me, but at what I point to, for in this is I myself, my mission, my nature, my calling; I am not the answer, but I know the way to the answer and I am bringing you to know it; I am not the content, but only the map, which by following you might leave the realm of omnipresent, all- encompassing superficiality and move into the depths and up to the heights of living, meaningful being. It is no coincidence that Daria Dugin’s second book is called The Depths and Heights of My Heart (Topi i vysi moego serdtsa, Moscow: ACT, 2023).

Daria always thought of herself as a sign and her philosophical works as a compiled guide. She did not pretend or claim that this sign would be the final and conclusive one, or that her map was complete and displayed all of the most important nodes and objects in the world of ideas. She was a modest thinker, she knew what philosophical tact is, what a boundary is, and what happens when you go beyond such a boundary. Hence why she was so attentive to the topic of the Frontier (to which another work by Daria is devoted). In her texts, talks, and presentations, she pointed only to those segments of the philosophical path that she knew or which she had not yet passed, but which drew her towards them, promising revelations, encounters, comprehensions, and maybe even bitter disappointments. But such is the philosophical life. Any and all of her experiences of this life are invaluable.

The Philosophical Hero

Daria is a philosopher furthermore because her whole life, from her birth to her tragic death, proceeded in complete harmony with the primal element of philosophy. The main point of orientation in our family is Tradition, and this means that philosophy is conceived primarily as religious, vertical, oriented towards God and heaven, where the beginnings and principles of thought must be sought. The absolute truth conveyed to us in the Gospel of John, “In the beginning was the Logos” (Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος), is the guiding star. Daria Dugina was killed by the enemy when we were returning from the Tradition Festival. Tradition is the beginning and the end, the alpha and the omega. In her philosophical fate, Daria’s omega, the point of end, was pierced by the same ray, the ray of the Logos.

Daria Dugina became a philosophical heroine. She descended into the world along the ray of the Logos and ascended back up along it into heaven. The seal of martyrdom was placed onto her thought, her mission, her intellectual life. Such is worth — and costs — a lot.

The ancient Greeks could not accept that a true thinker might leave forever, die, and disappear. They were sure that a devotee of the Logos, loyal to the very end, to the omega, does not die, but becomes a new star in the eternal, celestial horizon of ideas, or even becomes a god. Socrates and Plato were revered by entire generations of followers who were sensitive to philosophy as incarnations of Apollo, and the Neoplatonist Plotinus was seen as the figure of Rhadamanthus, the eternal judge who came into the world to remind people submerged in time of the unchanging radiance of eternity.

Christianity left such pagan notions behind, yet it raised the feat to an even higher, previously unthinkable pedestal. Now God himself, the Logos itself, came into the corporeal world, became a man, suffered, was killed, resurrected, and ascended to heaven, to the eternal throne due to him. After Jesus Christ, this path was followed by a whole host of Christian saints and martyrs. They set off to follow the Logos, suffered for Him, died in Him, were resurrected in Him, and ascended to heaven. In Christianity, moreover, no one merely disappears without a trace. Those who have given their lives for their friends, for Christ, the Son of God, for the Logos, and for luminous, vertical thought, are all the more alive and shall shine from the eternal heavens for those of us who remain here.

One must not only be born and live as a philosopher, but die as a philosopher. And to do so in full accordance with one’s spirit, one’s faith, with the sign pointing upwards to the heavens is the essence of the true thinker. A genuine philosopher cannot but be a hero. The tragic seal imprinted on the philosopher’s life is the highest recognition. Only that which grows out of suffering is genuine and worthy. Such is the lot of those in the world who carry within themselves something that is not of this world. This is the source of the philosophical grief that Daria lived so penetratingly, and which she pursued not as a girl, not as a child, but gallantly and courageously.

Eschatological Optimism: Towards Theory

The main topic of this book, which consists of Daria Dugina’s philosophical essays, is “eschatological optimism,” as is thematized in the title. It is best to follow Daria herself here, as she tries to define this notion not in strictly rational terms, but empirically and phenomenologically, sharing her experience of living and experiencing this idea and inviting those who are drawn to this experience. In some sense, Daria authored the concept of “eschatological optimism” as such. It is of no importance whether we find it among her favorite authors (Cioran, Evola, Jünger) or imagine it to be something original and the first in a line that would lead us to read philosophical and cultural theories from an altogether specific angle. The point is not in words, but in how certain terms, expressions, or phrases become a method, a means of deciphering, a basis for interpreting.

“Eschatological optimism” is a paradox. It is a combination of doomed fatalism and the triumph of free will, an acute experience of the world’s collapse and faith in the victory of the spirit, a faith which is rendered only more ardent by the fact that it has no confirmation. The eschatological optimist is capable of synthesizing and experiencing at once and to the extreme the highest degree of despair as well as an all- consuming, joyful hope. The end of the former is the beginning of the latter. The pain of the end is the joy of another beginning. But we, as humans belonging to two worlds at the same time, should not avoid suffering the doom of this world. Our calling is to suffer along with it, alongside its collapse, its imperfection, and its perversions and slide into the abyss. The human being is a suffering creature. This is not to be avoided. After all, such is our destiny, our fate. Otherwise, why would our God have suffered on the cross? He suffered, and that means that we should do the same. This world is already the end of a world, and this pain permeates all of its structures, all of its layers, all of its levels. If we are attentive, then we will read on these pages how being suffers, how the universe cries. Its tears are our souls, our thoughts, our laborious dreams.

But there is yet another side of things. Eternal heaven is so far away, so inaccessible, so unattainable, yet it is within us. To be more precise, if we are to be extremely keen to experiencing that which is not inside us, if we are to build our lives around this ontological perforation, this black hole, then one day a new star will be born within — the star of the hidden realm, the “un-evening” [nevechernii] light of resurrection. Then, at some turning point of grief, nearly imperceptibly to the eschatological optimist themself, the darkness will turn into light. Heaven will be at arm’s length. Unexpectedly and abruptly. Like an explosion.

Platonism and Christianity

Daria Dugina was a Platonic philosopher, a Platonist. To this we should add: she was an Orthodox Christian Platonic philosopher. Brought up since her childhood on the ideas of the Traditionalists (René Guénon, Julius Evola, Mircea Eliade, and their followers) as well as Orthodox Christian culture (Daria, like us, her parents, belonged to Edinoverie and to the Old Believers’ Rite of the Russian Orthodox Church tradition), Daria discovered Plato and the Platonists at the very beginning of her studies at the Faculty of Philosophy at Moscow State University. It all started with Dionysius the Areopagite, the pinnacle of Christian Platonism. Areopagitism became her guiding star allowing her to connect Orthodox Christian theology with the Platonic universe. The deeper she went in her studies in Platonism, the further she discovered an organic connection with Orthodoxy and with Traditionalism. The Traditionalist philosophers themselves mentioned Plato only in passing without focusing much attention on him. In Christianity, following the hasty and intellectually controversial judgments passed on Origen in the Justinian era, a steady distrust of Plato’s teachings took hold. The very fact that the foundation of Christian theology itself — Orthodoxy — in its terminology, conceptualization, structure, meaning, orientation, etc., was developed by the Alexandrian school and its direct successors, the Cappadocian Fathers (the most vibrant representatives of Christian Platonism), led to it finding itself in the shadow of sharp anti-Platonic attacks. Of course, this affair was aggravated by the Monophysites, the Monothelites, and later by the obviously unsuccessful theological seeking of the disciples of Michael Psellos and John Italus. Finally, in the Palamite polemic, the opponents of St. Gregory Palamas, Barlaam and Akindynos, tried to substantiate the criticism of hesychasm with reference to Plato. However, if we look deeper and we abstract from these historical vicissitudes, in which the cultural and even political context played a large role that was not directly connected to the world of ideas, then the unity of the attunement, verticality, and the unconditional devotion to heaven, eternity, and higher horizons of being brings Platonism close to Christianity beyond any doubt. The first Christian apologists were well aware of this, and the Cappadocian St. Basil the Great, the supreme authority of Christian Orthodoxy (and, in fact, a follower of Origen, whose texts he compiled into the first volumes of the Philokalia alongside his associates St. Gregory the Theologian and Gregory of Nysa), urged Christians to acquaint themselves with the works of the Hellenic teachers. Finally, if we turn to the Greek originals, then the Areopagitic texts are at times simply indistinguishable from the works of Proclus and his school.

When Daria discovered this, she was completely seized by Platonism, and in many ways she inspired those close and beloved to her — naturally, philosophers — to commit to in- depth studies in Platonism.

Moreover, Daria took note of the astonishing closeness between Plato, the Neoplatonists, and the European Traditionalists, between whom she discovered a complete unity of ontologies: the Traditionalists had described an ontology that is approximately and polemically opposite to that of the fragmentary and distorted ontologies of Modernity, and the Platonists had an extremely developed, detailed, and fully expounded ontology, one no worse than the Hindu Advaita-Vedanta. Daria thereby discovered the possibility of essentially expanding the language of Traditionalism, insofar as we can fully incorporate Platonism as a thoroughly correct version of traditional metaphysics into Traditionalist philosophy. For those who understand the meaning of language, this is simply an incredibly significant discovery.

In condensed form, all of these considerations are contained in this book, Eschatological Optimism, in which Platonism is treated and referenced in a whole section as well as throughout the various texts and discourses compiled into this volume.

Daria’s thought harmoniously and subtly synthesizes Orthodox Christianity, Traditionalism, and Platonism, strengthening and reinforcing what is paradigmatically common among them instead of putting them into contradiction and conflict. Daria even treats Julian the Apostate in the context of political Platonism and the metaphysics of Empire — the basis of the Emperor’s Katechontic mission in the pure Christian understanding — rather than in the sense of a polytheistic restoration. This is a bold move, but it is grounded in the whole structure of her philosophical worldview. It is not an attempt at revising Orthodox Christian tradition, which for Daria was to the very end the highest and only truth, but rather a drawing of attention to the paradigmatic likeness of the structure — and that is an altogether different matter.

The Poor Little Subject

Daria Dugina devoted much attention to the problem of the subject. Even in her early youth, she noticed, quite naively but with astonishing accuracy, that a weak subject predominates in Russian culture, in our society and people. She called such the “poor subject” or even the “poor little subject.” To be honest, we even teased her about this. After all, despite all the correctness of such a discernment, we thought it was not worth dwelling on. But this idea fascinated Daria, and she repeatedly returned to this formulation. In a womanly way, she felt sorry for this “poor Russian subject” that was so tender, helpless, and clumsy, yet so dear, kindred, and beloved. Daria could sympathize with and share the pain of another person. Even when there was nobody nearby who deserved care and compassion, she would manage to find someone. The concept of the “poor subject” became the expression of this deep feeling of her soul. She pitied not some person or creature, but a concept, an idea. Hers was a deep, spiritual, philosophical pity.

This concept conditioned her path in many ways. On the one hand, she felt that in none other than the “poor subject” lies some kind of truth that is difficult to formulate, some hidden revelation, some kind of difficult, tragic, painful truth. Pushkin’s protagonists were piercingly clear to her, especially Samson Vyrin from The Stationmaster, or Evgeny in The Bronze Horseman, the mad Akaky Akakievich in Gogol’s Overcoat, or the drunken Marmeladov in Crime and Punishment. Behind the feebleness of ordinary, weak Russians incapable of defending themselves, Daria erased their banality and divined their hidden greatness, their heroic fidelity to some hidden, unspoken truth and a secret, mysterious Russian message to the world. Sure, Russians are weak, feeble, and mad, but there is something else inside them, and this something else piercingly and acutely resounds to those whose ears are attuned to the Russian wave. Daria loved the “poor subject,” because only a woman, in her boundless, inexhaustible, pitying tenderness, in the infinity of her compassion, in her sacrificing, in her purely feminine majesty, so inaccessible to the other sex, can love such a subject.

At the same time, Daria carried within herself the will for a strong, steadfast, courageous, heroic subject. Russian weakness and poverty gave rise within her to an unbridled desire to make up for and seize such with her own strength. A powerful, strong- willed, deep, and active subject should be born not against, but out of such weakness. What is of foremost importance is to not become like the cold intellectualism of the West, which knows neither compassion nor pity, is deaf to feebleness and poverty, and is haughty and individualistic. This is not what Russian strength is about; this is not how the Russian subject is supposed to be built. The Russian subject is to be strong in sacrifice, courageous in serving the whole — the people, the state, the Church — and deep and wise not for the sake of boasting, but in order to pass on the light seen at the heights of contemplation to others, to the unfortunate prisoners at the bottom of the cave. A strong subject, a Russian hero, is first and foremost a sacrifice. This sacrificial victim knows that his fate is tragic, that his path is one of suffering, but he consciously chooses this path and wishes for no other path for himself.

Daria cultivated will, intellect, and deep, steadfast, powerful, and heroic subjectivity. This was her conscious choice. But this power that she accumulated and compelled herself to cultivate within was originally not for herself alone. By virtue of some kind of astonishing fatality, she knew that she was fated to become a hero, to sacrifice for the sake of the people and the Russian Idea. Her strong, powerful subjectivity was deliberately oriented towards surrendering itself to weakness, to igniting by its own fire the corruption of the weak little subjects of a semi- living society, so that they would be kindled and filled with her power which would become their own.

Who could have known that this fire would be the flame of a young philosopher’s car blown up by enemies when she was returning from the peaceful Tradition Festival at Pushkin’s Zakharovo estate. Even talking about this is horrific, but she and no other saw the path of the hero that she always wanted to become.

Daria Dugina’s Feminism

For Daria, the question of sex and gender was of great importance. Following the philosophy of Traditionalism and above all Julius Evola’s Metaphysics of Sex, she was raised on the fact that man and woman represent two metaphysical worlds. No direct analogies between them are reliable. Every detail, not to mention something more, carries a different meaning, a different purpose, a different form, and different substance in the world of man and in the world of woman. Daria saw in this the richness of being. It is enough to accept this, and instead of one universe, two open up before us. The relation between them is not at all reducible to the flat logic of power/subordination, completeness/lack, directness/curvature, presence/absence, etc. Everything is much more complicated, for each world has its own dimension, its own topology, its own semantic structures, its own languages and dialects. Daria seriously posed to herself the question of the language of women. After all, even when they are amongst themselves, women continue to speak the language of men. Only in rare moments — and above all when they are alone with infants — do women’s deeply concealed sounds and syllables break out. They are relics of a forgotten, lost, primordial mother tongue submerged in the depths of the unconscious.

Daria took an interest in feminism, and one of the sections of Eschatological Optimism is dedicated to this topic. Here Daria finds herself before a dilemma. Women’s desire to uphold their sovereignty in the face of toxic masculinity is understandable. There is something justified in it. After all, a woman is not a thing, not a slave, not property, not a second-class creature, and not an incorrigible fool — such is a male view that is, in fact, characteristic of a lower type of rude, carnal, primitive men. The higher the man, the more attentive he is to the feminine and the more delicate and subtle. But the fair posing of the question of women’s dignity is almost never or extremely rarely brought to the fore in modern feminism. Feminists most often slip into one of three extremes: they demand complete equality with men (and by taking the values of the male world to be criteria for the norm, they thereby abolish their own sex and simply become “men”); they establish matriarchy, which only parodies the brutal domination of men; or they call for the abolition of sex altogether as something deliberately bearing inequality and stand in favor of asexual cyborgs.

Daria believes that this is not right. There must be another way out. She finds it in the standpoint of a feminism which insists on the autonomy of the two worlds, male and female, masculine and feminine. There should be no prescriptions for the feminine world. A woman true to her nature can choose and most likely will choose service to God in monasticism, service to family, children, to a wonderful and heroic man, to an idea, to a cause, to the affirmation of higher values. In so doing, she does not betray her sex, but allows the infinite wealth inherent in her sexual nature to reveal itself. The highest destiny of a woman, as well as a man, as Daria’s beloved Plato said, is being a philosopher. Sure, woman is weaker and burdened with many worries, but this only means that she must work on herself more, keep up with everything and become even stronger, stronger than her weaknesses, and then her weaknesses will become her strengths, her surface will become her depth (as Nietzsche believed). This is a completely different feminism — Daria Dugina’s feminism, which is quite compatible with Orthodoxy, patriotism, and reverence for the family.

Postmodernism on the Attack

Daria Dugina was interested in contemporary philosophy, especially Postmodernity and Postmodernism. Of course, her truth was elsewhere — in Tradition, Orthodoxy, and Platonism — but some aspects of Postmodernity fascinated her. Daria fairly deeply studied Lacan, Deleuze, and object-oriented ontology. A whole section of Eschatological Optimism is devoted to these studies.

Daria was fascinated by Postmodernity’s entangled topos that has turned philosophical discourse into an ironic charade which, as it has unraveled, has not seen meanings cleared up and accumulated, but made more obscure, extinguished, flickering out on the farthest periphery, plunged into utter corporeal meaningless. For Daria Dugina, Postmodern philosophy and object-oriented ontology are the domain of philosophical demonology, analogous to the medieval legends of sorcerers’ and heresiarchs’ black miracles, a kind of Hammer of Witches which tells of what should not be done or uttered under any circumstances, but which some are nevertheless saying and doing. This is how a scout plunges into the completely alien and deeply disgusting identity of the enemy in order to peer into its final grounds. This is how Daria’s strategy in her research into Postmodernism can be interpreted. Her experience was one of metaphysical reconnaissance carried out in enemy territory with the aim of studying their structures, communications, their operations and supply systems. In order to fight an enemy, it is first and foremost necessary to understand him, and to not succumb to his hypnosis and propaganda (as, alas, the vast majority of the Russian philosophical community does), but also to not plug one’s ears and pretend that nothing is happening. It is happening. Armed with their own epistemological strategies, Postmodernity and object-oriented ontology are attacking the poor Russian subject and, taking advantage of the latter’s weakness, are immersing themselves into the corrupted networks of moderated and controlled perversion.

Postmodernists and the advocates of speculative realism are good in that they openly declare their intentions. Deleuze called for turning the human being into a schizophrenic (schizomass) which, in his option, will, upon escaping reason, no longer be subject to “capitalist exploitation,” and object-oriented ontologists call for abolishing the human being altogether and finally extinguishing even the residually smoldering subjectivity in man to make way for the triumph of Artificial Intelligence, neural networks, cyborgs, or some kind of deep ecology.

Daria was convinced that the Orthodox Christian thinker and Traditionalist philosopher is simply obliged to delve into figuring all of this out so that the exotic rhetoric does not take them by surprise and leave them defenseless. This is what she sorted out. And she generously shared the results of her quest with anyone interested.

Yet, Daria was only beginning to develop her studies on this front, and the most important, fundamental process of her systematic deconstruction of Postmodernity was abruptly cut short by her death. But it cannot end there. Daria Dugina persistently developed the philosophy of Traditionalism and drew upon her authorities and great predecessors. Her philosophical feat must be continued by those who take her place in the ranks. To this end, it is of principal importance to understand what she was heading towards. Upon dealing with the principles of her critique of Postmodernity and object-oriented ontology — with all the subtle ambiguity of her interpretations which partially played along with Postmodernist irony, turning it against those who imagined that the monopoly on the laughter that collapses structures belongs to them alone — her cause of deconstructing the pseudo-philosophy of modern and contemporary times can and must be continued. This is a testament for her unborn children, to all those who will take her place in the unbroken lineage of philosophers who have for centuries dwelled in the fields of the great Plato.

We are One in the Logos

To conclude this foreword, I would like to say the following. Those who only observe from the outside and do not plunge into the essence of thought might say to me: You as a philosopher are only attributing your own thoughts to your tragically killed daughter, and you won’t find or hear them in her own texts and speeches, because she was completely different, she was her own individual with her own worldview and her own convictions. Of course, Daria was completely independent and original in her views. However, like myself, like my family, like my teachers and my followers, her deep individuality did not consist of a reduction of intellect to private, individual reasoning. Heraclitus’s words — διὸ δεῖ ἕπεσθαι τῶι κοινῶι· ξυνὸς γὰρ ὁ κοινός. τοῦ λόγου δ’ ἐόντος ξυνοῦ ζώουσιν οἱ πολλοὶ ὡς ἰδίαν ἔχοντες φρόνησιν, “it is necessary to follow the common, but although reason [logos] is common and universal, the majority live as if they had their own individual reason [logos]” — were for Daria (and for all of us and for all of “our own”) the purest expression of the ultimate truth. The Logos cannot be the property of an individual. On the contrary, a person should belong to the Logos, follow it, honor it, and, if this following is true and correct, then we shall draw near to it as one, even while some differences remain. With Daria, we are one with the Logos, one in Christ and in His truth. We have been, are, and shall be.

Dasha is no more. But this is impossible. It just can’t be. I believe that there is no me and no us without her. No one can convince me of her absence. No arguments can serve to do so. On the contrary, this book, Eschatological Optimism, convinces us that she is still here. These are not merely her notes, but the pulses of her mind, her spirit, her soul. This is the concept of her philosophical life. This life had a beginning, but it has no end.

***

READ MORE: Daria Platonova Dugina, Eschatological Optimism (PRAV Publishing, 2023).