Putin’s Munich Speech: A Turning Point in Russian History

Primary tabs

Alexander Dugin discusses Vladimir Putin’s Munich speech in 2010 as a historic turning point, asserting Russia’s rejection of a unipolar world and advocating a multipolar global framework that acknowledges Russia’s sovereignty and geopolitical interests.

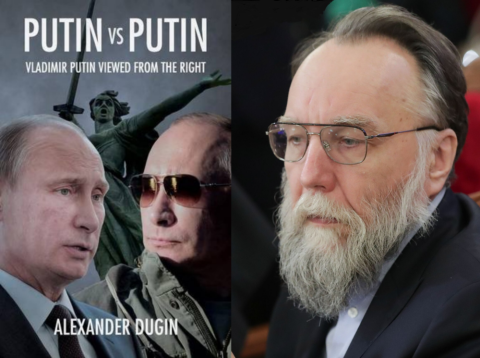

This is an excerpt from Alexander Dugin’s Putin vs Putin (Arktos, 2015).

Vladimir Putin’s speech in Munich1 became a turning point in contemporary Russian history. It would be a mistake to think that the Cold War ended in 1991. Rather, one should say that the Soviet Union unilaterally withdrew from the war. In doing so, it did not sign any documents and did not negotiate any terms. This withdrawal was presented to the Russian people as the end of the war. Imagine the following situation: two powers are fighting with each other. Suddenly one of them proclaims: ‘I am out of the war’, without specifying whether it considers itself the winner or the loser. A dubious situation arises: one of the sides withdraws from the conflict, thinking that the other will withdraw as well. Except the other side doesn’t. Notably, the former, who has already dismissed its army (the Warsaw treaty),2 tore down its bases (both in Eastern Europe and in the USSR) and began to concern itself with internal affairs, in effect finds itself in the position of the loser. ‘The winner’, in turn, starts to treat its opponent as the loser. But the political elite of the losing country does not tell its people that their country has lost, and continues to act like nothing happened. It makes it seem like the Cold War is over and it’s a tie.

This situation had persisted since Gorbachev and continued until Putin’s speech in Munich on 10 February 2007. The Americans have never stopped fighting the Cold War. They keep on advancing, expanding the NATO bloc and, at the same time, claiming everything that we aren’t keeping an eye on: first in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states, then in the Commonwealth of Independent States itself. In other words, the United States always has and always will be waging a Cold War against Russia.

This is why Putin, by and large, didn’t really say anything new in his Munich speech. Conversely, the Russian government during the Gorbachev and Yeltsin eras acted like a colonial administration, pretending that the US was not waging a Cold War against us, glossing over US occupations, and not allowing the people to mobilise themselves in order to obtain freedom and sovereignty. These leaders destroyed the people’s drive for resistance and victory by dulling their sense of awareness. During Yeltsin’s presidency, a completely opposite model was promoted: Russia was acting in line with NATO’s policy and betraying its own geopolitical essence. When Putin came to power, many of his statements and actions gave rise to speculations that he was more inclined to side with the Eurasian model and the multipolar world than with Yeltsin’s political course…

From the ‘Cool War’ to a ‘Hot Phase’

During his first presidency, Putin, under the guise of obedience to the occupation forces, pursued a policy of internal mobilisation. In other words, he was preparing an uprising. He was merely waiting for the right moment when he would be able to openly say to the world and his own people that the Cold War against Russia had never ended in the first place, and that, in kind, our country was still at war. He started off talking about the concept of ‘sovereign democracy’, and finally called a spade a spade in his Munich speech in 2007.

The concept of ‘sovereign democracy’3 became common in 2005-2006 and was one of the principal ideologemes during the presidential and Duma elections in 2007-2008.

At the time, I was contemplating the deconstruction of democracy and thought that this strange concept of ‘sovereign democracy’ should serve to remind us that democracy is not something that should be taken for granted. Its dogmatic status and refusal to acknowledge alternatives prevent the very possibility of a free philosophical discourse.

Democracy can be accepted, as well as rejected. It can be established, as well as disposed of. History has known perfect societies with no democracy and dreadful societies which had democracy, and vice versa. Democracy is a man-made project, a construct, a plan, but not a destiny. It can be rejected or accepted. It needs validation, an apologia. Without an apologia, democracy will have no sense. An undemocratic form of government should not be considered as the worst possible form of government. The ‘lesser of two evils’ formula is a propaganda ploy. Democracy is not the lesser of evils… it may be evil and may not be evil at all. Everything requires philosophical consideration. Only on the basis of the above assumptions is it possible to analyse democracy thoughtfully.

Let us consider the etymology of the word demos, since democracy means ‘rule of the demos’. Usually, this word is translated as ‘people’. But there were many synonyms of the word ‘people’ in use in the Greek language: ethnos, laos, phule, and so on. Demos was one of them, and it described a population: that is, people living on a specific territory.

Julius Pokorny’s4 Indo-European etymological dictionary5 states that the Greek word demos is derived from the Indo-European root * dā (*dǝ-), which means ‘to share’, ‘to divide’. Therefore, the very etymology of demos refers to something divided, sliced into separate fragments and placed on a certain territory. The Russian word with the closest meaning is население, ‘population’, but not ‘people’, because ‘people’ implies a cultural and linguistic unity, as well as a common historical existence and a certain destiny (predestination). A population can (theoretically) do without the above. A ‘population’ is everyone who has settled or has been settled on a particular territory, but not necessarily people who have roots or citizenship in that land.

Aristotle, who introduced the notion of democracy, had a somewhat negative attitude to it in its ‘Greek’ meaning. According to Aristotle, ‘democracy’ is equivalent to ‘rule of the masses’ and ‘ochlocracy’ (mob rule). As an alternative to democracy, the worst form of government, Aristotle discussed not only monarchy and aristocracy (‘the rule of one’ or ‘the rule of the best’, which he viewed positively), but also politeia (from the Greek ‘city-state’). Politeia, much like ‘democracy’, is the rule of many, although not on an indiscriminate basis. It is the rule of qualified, conscientious citizens, who stand out as a result of their significant cultural, genealogical, social and economic characteristics. Politeia is the self-rule of citizens on the basis of traditions and customs. Democracy is a chaotic agitation of rebellious masses. Politeia involves cultural unity: a common historical and religious base for citizens. Democracy can be established by an arbitrary set of atomised individuals, ‘divided’ into random sectors. Aristotle, in fact, mentions other forms of unjust rule — tyranny (the rule of a usurper) and oligarchy (the rule of a small group of rich scoundrels and corruptors). All negative forms of government are connected with each other: tyrants often draw upon democracy, just as oligarchs often appeal to it. Integrity, which is so important for Aristotle, lies within monarchy, aristocracy and politeia. Division, fragmentation, and atomisation are on the side of democracy.

The idea of division and atomisation was employed by modern philosophers to describe human societies and the state of man himself. With the concept of an ‘individual’, the indivisible, an ‘atom’, modern history was freed from metaphysics, authority, the rule of the Church and from morals. It freed humans from the divine care of theocentrism.

The modern era has established itself on the cult of ‘methodological individualism’, as opposed to ‘methodological holism’. It is the negation of the Only (God) and the recognition of the priority of the Many (individuals) that is the principal dogma of modernity and the main hypothesis of the modern era. In the postmodernism of our times this thesis remains undisputed.

In this context, the concept of ‘sovereign democracy’ in Russian politics circa 2005-2007 meant roughly the following: the Western world distributes and insists on democracy, referring to a very specific model that was established in Europe in the modern era. It is built around the principles of individualism and ‘liberty from’ — principles that have guided Western civilisation for almost three hundred years, since the modern era began. Russia is a non-individualistic country; its history and culture have always been based on integrity, being united, the common, and the collective (be it the people, communities, the Church, God, the state, or the Empire). Western democracy does not suit Russia because it is individualistic and is based on a rational, goal-oriented and assertive individual subject. We must have our own democracy — one that takes into account the peculiarities of our national pattern and national history. This is what the sovereignty of our choice and of our democracy is about.

It is interesting to note the way these arguments by Russian political commentators had touched upon the topic of a multipolar world before Vladimir Putin officially spoke of it in his 2007 Munich speech.

This speech was a turning point in Russian history. Its content was a direct reflection of the world as it really is: America is waging a ‘cool war’ on us. Even Western political scientists have said the same thing. The fact is that a Cold War is possible only in the case of a fully symmetrical weapons system, meaning that the adversaries must control equivalent spaces. For now, Russia is left with asymmetrical answers only. There is a possibility that this war can become a ‘warm war’ or even a ‘hot war’ at any moment. The anticipated attack on Iraq, which was in direct opposition to Russia’s strategic interests, was a step toward shifting the ‘cool war’ into a hot phase. If the US attacks Syria or Iran, America is actually threatening Russia.

Putin said it all in his Munich speech, thereby evoking a shift in Russian self-awareness. Prior to the speech in Munich, we had spent 15 years living under the impression that there was no ‘cool war’, thanks to our corrupt colonial government. They had convinced us that there was no unipolar world and that everybody was working toward a multipolar world. So, after this period of intellectual frenzy in which Russia found itself after Gorbachev and Yeltsin, the country started to come to its senses. People started to see things as they really are. The ‘period of confusion’ was over. In and of itself, this understanding of reality was actually quite sad: if we look at what we had been doing for two decades in light of Putin’s speech, we should be ashamed of ourselves. We had put ourselves in the hands of the occupation’s elite, which consisted of oligarchs, pro-Westerners and liberals who intentionally destroyed our strategic positions and tried to strip our country of its sovereignty.

The Munich Speech: A Foundation for Geopolitics

It would not be an overstatement to call Putin’s Munich speech a historic one. It had been decades since a Russian leader spoke so clearly and categorically about the future of international politics. In Munich, Vladimir Putin declared Russia’s principal stance as that of a world geopolitical force in the future world order. The theses voiced by Putin briefly covered, succinctly and decisively, the conclusions that I had drawn as far back as the mid-1990s in my book The Foundations of Geopolitics. The book was devoted to the fundamental conflict between the ‘land civilisation’ and the ‘sea civilisation’,6 and to the infeasibility of a unipolar world. The book stressed that Russia should lead the forces which would oppose unipolar globalisation and the spreading of Atlanticism embodied in the North Atlantic treaty (NATO). In Munich the President combined these fragmented statements into a concise and clear statement. In essence, Putin expressed his readiness to oppose US international policy.

During the 1980s, when the Soviet Union was still intact, and during the 1990s, when the Soviet Union disappeared (and, in fact, long before that, since Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt), America was taking strategic steps toward creating a unipolar world. The only question was whether it would share this global sovereignty with other countries or not. Putin challenged the contemporary state of affairs and the entire course of international politics. When such statements were made by Hugo Chávez, Kim Jong-il or Ahmadinejad, they were easily brushed off (although Ahmadinejad stood apart). When they are made by Russia, they are a game-changer.

When a country that possesses the second-largest nuclear arsenal in the world, occupies a huge territory, controls energy resources, and has a lengthy history of a national mission and opposition — essentially a ‘country-continent’, a civilisation — challenges the United States, NATO, the Energy Charter7 and the entire world order, it means that all masks come off. Putin stated that the unipolar world was absolutely inadmissible, and that the ballistic missile defence system that is being created in Europe by the US cannot be directed at North Korea — it is directed at us. Russia strongly opposes the construction of the BMD system and cannot ignore it. Putin said that NATO is not a partner but an enemy who is destabilising the political environment throughout its entire sphere of influence, and that the Energy Charter that Europe is forcing upon us, intending to ensure access to Russian energy resources without giving Russia access to European energy resources in return, is a humiliating, occupation-style agreement: ‘You give us everything and we give you nothing.’ That’s the way people negotiate with losers, who are expected to submit to the winner’s will. Putin essentially declared that Russia would be challenging the world order and paving the way for a geopolitical revolution — no more, no less.

Purchase Putin vs Putin here.

1. At the Munich Conference on Security Policy on 12 February 2007, Putin condemned the order represented by the unipolar world, calling for multipolarity, and accused the US of overstepping its bounds. The complete text is available here.

2. The Treaty of Warsaw established the Warsaw Pact in 1955, which was the Soviet answer to NATO by providing a treaty of mutual defence among the Communist states in Europe that were under Soviet domination.

3. This term has been widely used with several different meanings starting from the eighteenth century. Rousseau, for example, used the words démocratie souveraine to denote the sovereign power of the people; in America in the nineteenth century the ‘party of sovereign democracy’ was called the Democratic Party. — AD

4. Julius Pokorny (1887-1970) was an Austrian linguist.

5. Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, 4 vols. (Bern: Francke, 1951-1969).

6. This is a key dichotomy in geopolitical thought, as first established by Sir Halford Mackinder. Carl Schmitt wrote, ‘World history is the history of the wars waged by maritime powers against land or continental powers and by land powers against sea or maritime powers’, in Land and Sea (Washington, DC: Plutarch Press, 1997).

7. The Energy Charter Treaty was signed at the end of 1991 with the intention of integrating the energy resources of the former Eastern bloc territories into the global marketplace. Russia has refused to ratify it because it sees it as unfairly balanced against its national interests.