The Problem of "Nothing" in Philosophy

Primary tabs

This article is devoted to the most important philosophical problem – the problem of Nothing. At first glance, nothing is easier than nothing, but in fact, nothing is more complicated. When a person begins to think about being, including about his own being, about his life, he will sooner or later come across the topic of the border. Being is. But in order to truly appreciate it, it is necessary to correlate it with something. This is where Nothing comes in.

Outside of being there is only Nothing. And outside of life, there is its downside – our own Nothing – death.

Any responsible thought, whatever it may be directed, one way or another – frontally or tangentially – is directed to Nothing. The colossal tension that is required for being is thrown into nothing. When being can no longer be, it collapses. But since being is the most general of affirmations, it can fall only into the most general of negations.

Nothing becomes the focus of the greatest German philosopher Martin Heidegger. The human presence in the world takes on real meaning and real astringency, and this is what is put into the concept of existence when it encounters death. We begin to become keenly aware of presence only in the face of absence. While death is somewhere far away from us, hidden by many veils, our life is a calm and deep sleep. Only death – a direct collision with it – in ourselves or in the case of loved ones – can awaken us. Only when the doctor informs us of a fatal diagnosis, the fact that we are – still is, still, some time is – finally reach our consciousness. Nothing that now stands close to us brings us back to the fact of life.

In the face of death, we realize that we are finite. But finiteness is a form, a border, a distinction. The Greeks clearly understood that the finite is spirit, while the infinite is only matter. This means that only the form isolated from the surrounding – the Russian word “image” means cut off, selected, torn out – is truly valuable. And this value in its separateness, isolation – in the fact that it is placed on the border with Nothing. Awareness of our finitude – as well as the finiteness of anything and even the whole world – is for the first time a truly full-fledged experience, an experience that makes us human. It is only in contrast to the abyss of Nothing that things – doomed and ready to fall into the abyss at any moment – begin to tell us about their essence. The finite is beautiful precisely because of its finitude.

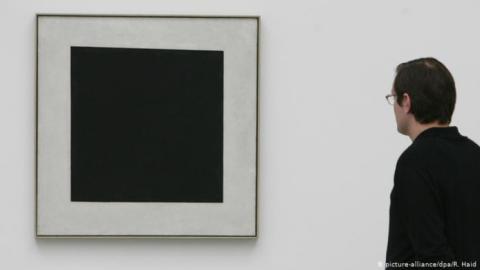

Therefore, Nothing also has an aesthetic side: it helps us understand the desperate and doomed nostalgia of true beauty. Beauty in the face of imminent doom.

Nietzsche believed that the modern world, and above all the Western world of modern times, is a civilization of nihilism. Nihilism is Latin nihil, meaning “nothing.” But he meant by this something else – not actually nothing, but the insignificance of modern Western values. They are too small and poor. They are nothing at all. They are rather banality, triviality, routine, petty. Modern man is incapable of pure experience of Nothing. If he were capable, he would live a full dangerous, and vibrant life. But the nihilist prefers to cringe, plunge into the smallest problems of caring for his puny self, so as not to come face to face with the abyss. Therefore, a modern man hysterically longs for physical immortality – at any cost – freezing, uploading to a cloud server, merging with artificial intelligence and global neural networks.

The thought of Nothing leaves culture and civilization along with the thought of Being. They are inextricably linked to each other. The last people are no longer capable of either one or the other. They cannot decide to be or not to be. Therefore, they do not live and do not die, trying to erase the boundaries, to arrange for themselves such an existence where there will be no breaks, hierarchies, falls, and ups. Dead life or living death. No sharp corners or sharp edges.

Looking at the world around us, at the modern people inhabiting it – or are they already electronic shadows? – there can hardly still be a glimmer of hope that the new beginning of philosophy has a chance. Philosophy is a matter of exceptional higher beings, in which tremendous forces have accumulated and exploded from within, spilled over the masses, epochs, peoples, cultures, and generations. Only then is a philosopher born, relying on a great thought and crystal horror. And of course, the first thing he poses before himself and before everyone else is the great question of Nothing.

Leibniz said: “Why is there something and not nothing?”

Jean Baudrillard put the question differently: “Why is there nothing else instead of something?”