Geopolitics: Theories, Concepts, Schools, and Debates

Primary tabs

(2-nd lecture in China Institute of Fudan University of Shanghai)

Geopolitics is a separate branch of strategic analysis. There are some links between International Relations theories and geopolitical theories, but Geopolitics is an absolutely original and independent field of strategic thinking and analysis. In this lecture, we are going to speak about the paradigms, concepts, schools, and main debates of geopolitics.

Geopolitics can be defined as a discipline that studies the relations and interactions between Spaces (Territories), States, Civilizations, Peoples, and Economics. This is a much broader context than that in International Relations, because theories of International Relations study only state-to-state relations. Geopolitics is much broader. First of all, it is centered around the relations between the state and space (territory) - and not only, but also culture-to-culture and people-to-people, all put into space. Space in geopolitics plays the same role as time for history. Geopolitical analysis is based on the centrality of space.

Space, in any sense, not only the material, is synchronicity. It is something that happens simultaneously. It is a synchronistic, not diachronistic approach. Historically, Geopolitics was developed from political geography and “anthropogeography”. It is a kind of political and human geography. Both terms were introduced in the 19th century by the German professor Friedrich Ratzel (1844-1904). Political geography means the relation between the state and territory, or space. The same Ratzel also used in his research the term anthropogeography, which means human geography. The anthropos, or man, is the most important here. In International Relations, nobody speaks about man or the human, but only the state. In Geopolitics, this is not so. Geopolitics tries to involve more levels of analysis than International Relations. This is why there have been problems with this discipline, because some scholars think it is too broad and includes too many levels in one concept, and so is not a precise science.

The next element in Geopolitics was the idea of the Swedish scholar Rudolf Kjellen (1864-1922). He proposed the idea that the state is a living being. This was an organic attitude towards the state. If there are living beings that move, then states move, or they have certain relations to the earth. This is an organicist concept. Kjellen and Ratzel belonged to the same philosophical school of organicism. They considered life, including political life, as something natural, not mechanical, but organic.

So what is the space of Geopolitics? It is qualitative, not quantitative. It is not “physical” space or “scientific” space. The quality of space is something like “life-space.” The concept of living space, or Lebensraum, was introduced by Ratzel. Afterwards, the term was used to mean a space which a growing people needs to occupy in order to satisfy needs. But that was a practical, pragmatic use of the term. Originally, Lebensraum, in the context of Ratzel’s ideas, meant precisely the space that lives - “living space”, in an organic attitude that is qualitative. Space is quality, where orientations do matter. This is much more of Aristotelian space than the space of modern physics. This is quantum-mechanical space, with different orientations. Space is different if you go to the North, South, East, or West - they are not relative concepts. There is a kind of absolute South or absolute North, absolute West, or absolute East. This space is a kind of category charged with proper characteristics. Space or territory is destiny. With such an attitude, space obtains a kind of historical meaning. Space is not indifferent; it is a very special, organic category. Space is also more important than time. This remark, as well, makes Geopolitics a post-modern discipline, because modernity is centered around time, history, and how everything is changing in the irreversible process of time and progress.

Geopolitics affirms that the most important category of human life and political relations is space. If you, your country, your culture, or your people, live in one kind of space, it will have special values, special politics, and special political organization - if, for example, you live on an island or in a coastal space, you will be obliged to have a different political system, cultural set of values, and so on.

Space, as the foundation of strategy, was also evaluated by the pragmatist and American admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914). The term “Geopolitics” was used for the first time by the Rudolf Kjellen; “political geography” and “anthropogeography” by Ratzel, and “geostrategy” by Mahan. These are the founding fathers or forerunners of Geopolitics.

But properly speaking, Geopolitics as a discipline was formed later, in the beginning of the 20th century. The context of the birth of Geopolitics was British imperial strategy. The real founder of Geopolitics was the British Sir Halford Mackinder, an English imperialist and partisan and promoter of reinforcing the British empire. He thought about the basic principles of the British imperial strategy, and tried to conceptualize them, basing himself on the political geography of Ratzel and the geostrategy of Mahan, and other authors - some British, some Americans.

The context is very important. Geopolitics as a discipline was born in the context of the British Empire in the beginning of the 20th century when the British Empire was still flourishing - not at the end or amidst decline, but at what might have been the peak of the British Empire, when the Britons ruled the world through the oceans, and had such colonies as India, China - which was almost a colony, not formally, but under Great British influence - Japan, Iran, the Middle East, Turkey, and almost all of Africa. Whereas the German colonies there were very small, the French and Britain shared most of Africa. The British Empire was alive and flourishing. The context of Geopolitics was thus the “Great Game.”

The “Great Game” was the idea that the most important enemy of the British Empire, just before the “age of geopolitics”, was Imperial Russia, which exercised growing control over Central Asia and threatened English colonies in the Middle East and India, trying to go South to Afghanistan, and also considering Russian expansion in the Caucasus - all of this growing power of Russia was considered the main enemy of the British Empire. This was the “Great Game.” Many aspects of global international geopolitics during the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries can be explained in terms of the Great Game.

It is British imperial strategy, including the Great Game, that was the context of the birth of Geopolitics. The British Empire needed to control trade routes on the continent, but mostly throughout the oceans and seas, as the power of the British Empire was based on the control of trade routes. That was almost the “law” - that the British Empire control trade routes throughout all the world. That was the basic aspect of British strategy, the system of colonies, as Britain controlled and exploited many colonies in Africa, Asia, and so on. The idea, one of the main concerns of British imperialism, was to conserve the British Empire. Geopolitics was born as the theoretical reflection on Anglo-Saxon imperialism. It was a purely Western, imperialist approach. That was the context. It is very important to put science and methods in concrete historical conditions.

The real founder of Geopolitics, Sir Halford John Mackinder, was a political geographer as well as founder of the London School of Economics. He was one of the leading thinkers of British imperialism. In trying to put together all the threats, principles, perspectives, and “logic” of British imperialism, as well as trying to prepare its future in a practical way, Mackinder came to the first vision that was a kind of result of previous approaches to political geography. He published in 1904 in England a very important text composed of small articles, called The Geographical Pivot of History. In these articles, Mackinder laid out the real basis and principles of Geopolitics. We can speak of political geography before Mackinder, but we can speak of Geopolitics sensu stricto only after Mackinder. The line is drawn between the preparation and the creation of the scientific method. Mackinder is a central figure, and that is the main view up to now. His actuality is absolute. We cannot dismiss Mackinder. There is no Geopolitics except Mackinder’s - like in Islam, there is no God but Allah. Mackinder created this science, this method, based on previous ideas, theories, and doctrines, but here is precisely the essence of Geopolitics: Mackinder affirmed that there is a fundamental opposition between two global powers - and that is Geopolitics, precisely.

There is Land Power, identified as Heartland, the “geographical pivot” or “axis” of history. All history moves around this pivot, this axis, this Heartland. History is a process, a dynamic, and here is the point of “no dynamics”, the static point, the pivot, around which the wheel moves. That is Land Power.

There is Sea Power, which is precisely history. History, or time, is Sea Power. Eternity or the unmoved point is Heartland or Land Power. They represent two kinds of civilization. Land Power is based on constancy and eternity, as Land is fixed, doesn’t move, it is fixed space. It is fixedness itself, which is what Mackinder understood by Land Power. Sea Power is something that moves.

This dualism served Mackinder to explain the meaning of history. According to Mackinder, the fight or dualism between Land Power and Sea Power is the key to understanding history. We can see that this is exactly a kind of explanation or theorization of the Great Game. But this is also Mackinder’s generalization, because it is not only an explanation of the Great Game. The Great Game - which saw the British Empire trying to control the seas and oceans against the Russian Empire - was a concrete, historical, strategic moment. But Mackinder generalized that the Great Game reflects something deeper, something universal, the basic principles of how human history goes on. This is the basic principle of Geopolitics.

When Mackinder tried to apply his ideas to history, he discovered that there is not only the British and Russian confrontation of the last centuries that can be explained by this geopolitical map, but he saw Sea Power in history, and identified Sea Power in: Athens, as coastal, as a maritime sea power, in Carthage, the opponent of Rome in the Punic Wars, in Venice as the sea power and trade civilization, in the Dutch colonial empire, and finally in Great Britain. This was a kind of geopolitical continuity between different forms of Sea Power in history. So it is not only an explanation of the Great Game, but is a law. All Sea Powers in history were based on trade, on oligarchies, on technical development, and on control over seas, not land - because Sea Power never goes too deep into the continent. They control the continent by controlling the coast. The coast is much more important than the continental mass. That is, in the final analysis, the control of all space where humans live “from outside”, from the seas and oceans. The standpoint of Ocean, Sea, or Water, is the main element. This is the power of Water, where you cannot trace borders. There is nothing fixed in Water. The ocean, sea, and lakes are ever-changing space. You cannot domesticate creatures living in water. You can only fish them. You cannot feed yourself freely in the water. You need a ship - something artificial. That is the difference between the nature of Water and Earth. Earth is stable. You feel good, safe, and secure on the earth, and you can domesticate animals. The Earth is a kind of natural ambience, while the Ocean is unnatural. You need some kind of technology in order to be there, such as a ship. There is a kind of alienation from space, from ambience, that is at the center of Sea Power. Sea Power already in Mackinder’s work obtains a kind of metaphysical or cultural dimension. It is not only about the Great Game and British imperial strategy - it is about something much deeper. This was expounded only in small remarks in these articles, but it was absolutely underlying.

Land Power in history is quite the opposite. It is Sparta fighting against Athens in the Peloponnesian War. It is Rome against Carthage in the Punic Wars. It is Austria, Germany, and Russia against Western - English and French - imperialism. This analysis is much broader than concrete situations. Mackinder proposed the key to deciphering the logic of history, namely, that all human history is based on this kind of cosmology or mythology, a political mythology of two opposite principles fighting against each other and trying to win - sometimes Sparta wins, sometimes Athens, sometimes Rome, sometimes Carthage, and so on, sometimes Russia, sometimes Britain. There is a balance, an everlasting war of continents.

Already in Mackinder’s works, Sea Power means trade, liberalism, democracy, progress, technical innovation, oligarchy, science, adventure, the entrepreneur’s spirit, and capitalism. All these marks or characteristics created capitalism. Capitalism was born in Britain during its colonial experience. Sea Power is linked to liberal capitalism, to democracy. Sea Power thus also obtains a political and ideological dimension already in Mackinder. This is why Sea Power is “good” for capitalism. Here arises the self-fulfilling prophecy: Sea Power is progress, Land Power is regress or stagnation. Land Power represents force, conservatism, hierarchy, order, ascetics as morals, aristocracy, religion, ethics, and stability. If we compare these concepts, then it is not necessarily socialism. It is something that is not liberalism. It could be a traditional empire, a pre-modern or conservative society, but it could be socialism as well. Everything that is not capitalism and liberalism can be Land Power. This is precisely geopolitics.

The modern geopolitics of the 21st century is the same. It is still good old Mackinder’s point of view. Here we see the main terms and concepts of geopolitics.

Rimland is a very important concept, because it is the coastal zone. In geopolitics, Rimland is precisely the most interesting part of the structure of space, because there is sea space, land space, and Rimland space, which is something “between” land and sea. The coast of Rimland can be controlled from the sea, or from land. Who controls Rimland, controls everything.

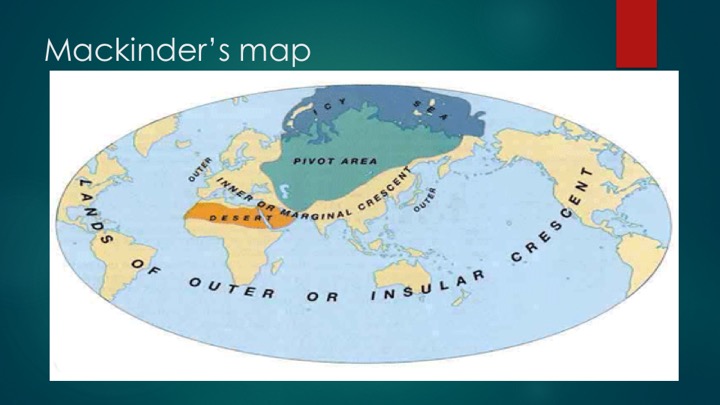

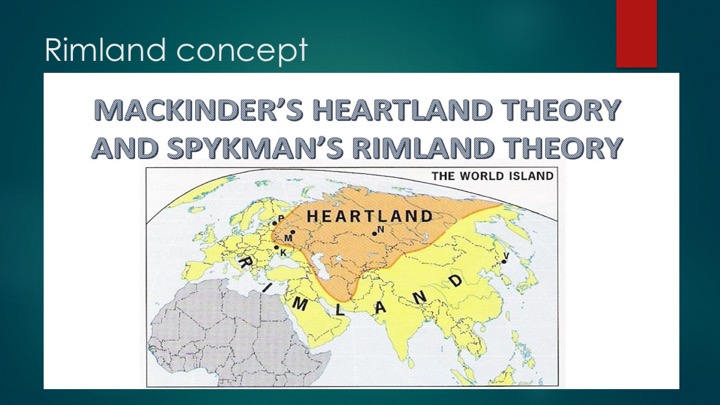

Here we can see the famous map of Mackinder, which was published in National Geographic in his article “The Geographical Pivot of History.” Here we see all of geopolitics in one map. It is so “classic” and so fundamental that today all who study geopolitics and apply geopolitical analysis to the modern situation still use this map, drawn in the beginning of the 20th century. This map, drawn more than a hundred years ago, is so actual that it is a kind of prophetic map. What we see here is Sea Power in what is called the Outer and Insular Crescent. This is the territory controlled by the British Empire and the Anglo-Saxon world. There is the pivot area, the same as Heartland, which is the landmass of Land Power. Here resides Land Power. And there is the Inner or Marginal Crescent, which is Rimland or the coastal area.

World history begins when both Land Power and Sea Power have acquired planetary dimensions. Earlier, the fight was on a reduced scale, but now it has acquired a planetary dimension, and there is only one explanation for what is happening on the planetary level: Sea Power is fighting against Land Power, trying to control the Inner or Marginal Crescent. The object of the fight between the two geopolitical powers, according to Mackinder, is the control of this zone, which could be controlled in one of two ways. The first is by Sea Power, which means that the metropolis, the center of the British Empire, is the master of all this space. Really, actually, in the beginning of the 20th century, all of this space was controlled by the British Empire. They needed (and need) to control Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Iran, India, at least the coastal part of China, Japan, and the part of the Far East that belongs to Russia. The idea was that the Inner Crescent, or Rimland, should be controlled by Sea Power, and that is the way to global domination by the Anglo-Saxon world. The conceptualization of the British Empire led Mackinder to this conclusion, and drawing this map was the foundational act of the creation of Geopolitics.

But what should Land Power do in the field of history? Mackinder honestly recognized that Land Power will fight back. Land Power, or Heartland, will try to do quite the opposite: to expand its power to the West, to conquer Western Europe, or all of Europe, impose its influence in the Caucasus, the Middle East, and Turkey, trying to use the territory of declining Turkey, and Heartland will try to destroy the British Empire’s control over Afghanistan, Central Asia, and India and, coming to China, to eject British Empire there, as well as in Japan. This was a kind of Great Game, balanced on a planetary scale with - most importantly - some philosophical dimension. Mackinder’s law was: Whoever controls Eastern Europe, controls Heartland, and whoever controls Heartland, rules the world. For Mackinder, it was crucial to control all of Heartland, or Land Power. Eastern Europe is only part of the truth, because all the Inner Crescent should be controlled by Sea Power.

But let us concentrate on this part of the sentence: “Whoever controls Heartland, rules the world.” This is the most important point. If Heartland is controlled from outside, the world is ruled by Sea Power. That means the democratic ideal, progress, modernity, and capitalism on a global scale. If Heartland is ruled by itself, by Land Power, it is something opposite: eternity, tradition, order, hierarchy, conservatism.

In Mackinder’s eyes, Heartland is an object. This object begins with Eastern Europe, as in the Inner Crescent, the coastal line of Eurasia. If the control of this coastal line or zone is strong enough, there is no possibility for direct confrontation between Eurasia, or Heartland, and Sea Power. Heartland becomes an object. But of Heartland. But if Heartland begins to be a subject, affirms itself as a geopolitical subject, is awakened or wakes up on its own, then there is a problem for the global domination of the British Empire. This was the main rule of geopolitics from then on. The fight for Eurasia is an application of this principle.

Mackinder’s follower, Nicholas Spykman (1893-1943), developed his theory of a kind of enlarged version of Mackinder’s, with the emphasis put on Rimland. Spykman said: Whoever controls Rimland, controls Herartland. Whoever controls Heartland, rules the world.” Mackinder was concentrated on Eastern Europe - after all, he was a high commissar of the entente in Ukraine, trying to divide and separate Ukraine from the Russian Empire. The same idea was taken over by Brzezinski and put into practice in 2014 on the Maidan. We are living inside Mackinder’s world, and we cannot get out of it.

Spykman said that we need to attach the main importance to Rimland in general. In order to rule the world in general, we should separate the Far East from Russia, exercise all control over China from the sea, control the Middle east, Northern Africa, India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, and all Eu

This is the map of the American mind. American strategy follows all of this line. These maps were drawn in the beginning of the 20th century, and this one in the 1920’s. They are so actual today. In the Anglo-Saxon vision, Sea Power is the subject and Land Power is the object. In 2005 I met Zbigniew Brzezinski in Washington, and there was a chessboard between us. I asked: “Mr. Brzezinski, do you consider the game of chess to be for two players?” He said: “No, it is for one.” That is the typical Western understanding, the Anglo-Saxon vision, of geopolitics. Chess is a game for one player, i.e., there is only one subject, and the other is not a player, but an object, whose hand must be moved. That is the basic attitude of the Anglo-Saxon vision of geopolitics. The main goal of Anglo-Saxon geopolitics is to surround Heartland by controlling Rimland, preventing Heartland from gaining access to the warm seas and breaking through the coastal blockade. The main goal is to rule the world by controlling Eurasia from the sea.

The future decline of Great Britain and the rise of the United States was predicted already in the end of the 19th century by some British imperialists, such as Sir Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) and his group, the Round Table. Admiral Mahan, as I have already said, considered the US to be Sea Power. It was not evident that the US was a Sea Power when Mackinder wrote his first article. He considered North America to be a kind of Land Power - isolationist, outside of global politics, and not in competition with Great Britain, but a marginal, peripheral space. But Mahan considered the United States, based on the growth of its navy, to be Sea Power. After Woodrow Wilson involved the US in the First World War, there began a very important geopolitical event or process: the shift of the center of Sea Power from Great Britain to the United States of America. That was accomplished over 20 years from the end of the First World War to the end of the Second World War. During this gap of time, all of Great Britain’s colonies were ‘given’ to the United States. There was a shift of the center of global domination inside the Anglo-Saxon space from Great Britain to the United States. That was the main event on the geopolitical level.

Very symbolically, Mackinder’s last article was published in an American journal, Foreign Affairs, whose editor’s organization, the Council on Foreign Relations, was created by the American elite just after the First World War in order to promote the Wilsonian vision of the United States as a global power operating in defense of capitalism, democracy, and so on. That was a theoretical, intellectual shift of the center of decision-making and the subject. This was a kind of transition of Sea Power. After that, Great Britain became the “old power”, the “senior”, “old man” tending his garden who offers some advice, but is not the real subject.

The real subject, from now on, from the first half of the 20th century, has shifted from Great Britain to the United States. Everything that Mackinder said about the strategy of Great Britain was applied, point by point and word by word, to the United States of America, above all in the second half of the 20th century. Before the founding of the Council on Foreign Relations, the United States did not “think of the world”; they had no foreign relations, and were absolutely concentrated on their internal issues before the First World War, before Wilson and his 11 points which declared that the United States of America should be a global power and global defender of liberalism, capitalism, democracy - precisely Sea Power. After the Second World War, the United States became the main, the only Sea Power par excellence. The rest became objects or tools in the hands of the Americans.

The first to carefully read the ideas of Mackinder were the Germans - not the Russians, who were involved in other intellectual and political problems. The Germans awakened to geopolitics and, within the first 20 to 30 years of the 20th century, began to read Mackinder and accept geopolitics. First there was Karl Haushofer (1869-1946), a German political geographer and general who was military attaché in Japan during the 1920’s. He brought back with him from Japan an interesting word 地缘政治 chi sei gaku, or “geopolitics.” He discovered and accepted the ideas of Mackinder afterwards, and recognized Germany, just as Mackinder affirmed, to be part of the Continent, to be Land Power.

Thus Haushofer began to develop the concept of how to create a Continental geopolitics, not as an object of Anglo-Saxons, but as a subject that will fight back consciously, not only as a tool, but as a kind of conscious power. His idea was exactly opposite to that of Hitler, as Haushofer said that there are only two possibilities for Germany. First, Germany is part of the Continent, or Land Power; it is conservative, traditional, hierarchical, and so on, has almost no colonies or “progress”, but is a traditional society. And if this is so, according to Haushofer, then Germany must be aligned in an axis, on which Haushofer published the article “The Berlin-Moscow-Tokyo Axis.” So, in order to be Land Power in its proper dimension, Germany should be allied with Russia - then, Nazi Germany should be allied with Communist Russia. This was the law of geopolitics that went against Hitler’s idea. But Haushofer said that if you want to follow the rules of geopolitics, you could come to the side of Sea Power, and in that case, Germany should conclude a treaty or alliance with the British and the Americans. But you cannot fight [on two fronts], or you will be destroyed - that was Haushofer’s prophetic saying. Geopolitics is therefore a kind of prophecy that is always fulfilled, whether ignored or open. Hausehofer told Hitler to find a way for an alliance with Russia, as was tried in the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, or with the West, as was tried with the Munich agreement between Western countries and Germany. The only thing that was geopolitically impossible was to fight on two lines - this was a geopolitical heresy, according to Haushofer. That was the German school that enriched geopolitics by creating new doctrines, new texts, new intellectual analysis, based on the acceptance of Mackinder’s analysis.

But a deeper understanding of geopolitics, Land Power and Sea Power, was given by another German philosopher, who is much more serious and profound than Karl Haushofer: Carl Schmitt (1888-1985). Schmitt was the greatest political thinker of the 20th century. He is known in all countries and universities of Europe, except in Germany, where he is prohibited. In the United States there is huge interest in Schmitt, and his follower Leo Strauss is considered the teacher of the Neo-Conservatives. There is a huge following of Carl Schmitt on the left as well, on the part of both the post-modern European left and the Latin American, by communists, anarchists, etc. He is the most read author in political science, and I am very happy that he is very well known in China. In Russia he is very popular as well.

In his book Land und Meer, Carl Schmitt deepened the understanding of what Land and Sea are. He used the biblical names Leviathan, the serpent of the sea, and Behemoth, the Land Power. The fight between Sea Power and Land Power was presented by Schmitt as the eschatological fight between Leviathan and Behemoth, two great monsters, that correspond to two opposite world-visions, or Weltanschauungen in German. He made a clear identification between Sea Power and modernity, capitalism, liberalism, democracy, materialism, modern science - all of these were a kind of ‘result’ of Sea Power. Carl Schmitt gave to the concept of Sea Power a huge, new meaning, that was a development of what Mackinder already had in mind, but was so brilliantly exposed that it transformed geopolitics into a philosophical approach and political philosophy, not only on the strategic map.

The same was declared by the British conservative author - a Catholic like Schmitt - Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936), who had two wives, both of whom were Serbian. Here as well, geopolitics acquired a metaphysical dimension. The Great War of Continents was considered to be a kind of eschatological, biblical battle for the End Times. It was not only about who controls Heartland and the world, but about what the goal of controlling such is. Carl Schmitt asked what is the goal to control - not power in itself, not only in a pragmatic sense, not as a power play, but as something deeper, as the final battle for the End Times, which in the Christian vision means the Kingdom of the Antichrist or the future Kingdom of Christ. This was a Christian, moral attitude added here. With that dimension, geopolitics obtained an eschatological dimension. Eschatology is the science of the end times, or what should happen as the result of history, at the end of history, in the Hegelian, not Fukuyaman sense.

The result of the Second World War was that Hitler totally neglected Karl Haushofer’s advice. There was no more Germany, no more Hitler, no more National Socialism, because of the suicidal war that cost humanity many millions of victims. Just after the Second World War, the Cold War started, where there was again a pure illustration of the classic map of geopolitics. There was the Soviet camp, of which China was a part, the socialist camp, against the capitalist camp. There was a moment when the Soviet camp and communist, anti-capitalist countries acquired the geopolitical dimension of Behemoth. Communism was Behemothic in some ways. It was Land Power. That’s why communism won not in the industrial, liberal countries which had a big amount of proletarians, but in peasant, agrarian countries like Russia or China - because they were Land Powers. Communism won in Land Power, in the context of anti-liberal, anti-Western, anti-Sea Power. That is the geopolitical explanation of the Cold War.

But the science of geopolitics, and the destiny and fate of this science, was different. In the United States, it was considered to be the main strategy, used always. They did not stop ever since Mackinder and Spykman’s times to use geopolitics as a basic vision of what is going on in the world and politics. But with the German effort to create an alternative geopolitics with the Continent as the subject, this experience bore a kind of demonization due to Haushofer’s relations with Hitler and the crimes committed by the Nazis. The Continental part of geopolitics was destroyed as a “pseudo-science”, while the Anglo-Saxon part of geopolitics continued to be accepted as a main strategy. So, after the Second World War, geopolitics came to have two meanings: (1) something completely rational and positive in the United States, and (2) something impossible, Nazi, and fascist outside of the United States and England. This is precisely like someone who wants to always win in a game of chess - the best solution is to not teach the other how to play. This is the “game of one”, as Brzezinski honestly explained.

Geopolitics was demonized for Europe, but taken as a normal tool for elite-learning in the United States. That is why Brzezinski, Kissinger, the Trilateral Commission, and the Council on Foreign Relations think exactly with the same map and concepts, but geopolitics is prohibited for the others. It is as if there are two geopolitics: “geopolitics” in English, which is a good, correct, and rational science, and German Geopolitik which is pseudo-science. If you look at Sea Power from Land Power, it is “pseudo-science.” If you look at Land Power from the standpoint of Sea Power, it is “science.” This is completely biased by virtue of standpoint.

Unluckily, in the Soviet Union, because of Haushofer’s reputation as well, geopolitics was considered a “bourgeois science.” It was prohibited as well, so we lost Continental geopolitics altogether. There was Sea Power geopolitics, while everyone else was left without geopolitics. So there was a reduced geopolitical awareness on the part of Land, considered to be an object. We do not teach dogs or cats human language or science, so we consider them to be “stupid.” The same is the case with geopolitics. While some declare that geopolitics should be reserved for the Anglo-Saxon ruling elite, they treat the others as enemies who should not be taught this “pseudo-science.” This is why there are so many debates on geopolitics, because it is a prohibited science for the Other, while in the Anglo-Saxon world, it is flourishing as a normal and necessary tool for the learning of the Anglo-Saxon, American elite.

After the fall of communism, Soviet, Russian society lost an understanding of what is going on. Everybody felt that something had gone wrong, but nobody had any explanation. We lost a line. We were no longer communists, but were capitalists and liberals left wondering why NATO is expanding, not accepting us in their club, continuing to still treat us as an enemy after the destruction of the Warsaw Pact and Soviet countries. We were “liberating” Eastern Europe, including some parts of the Soviet Union, while NATO tried to get them, still expanding. Before the North Atlantic alliance was a sea power, fighting on the geopolitical level of Land Power represented on the ideological level by the communists. After the fall of the Soviet Union, there was no longer any “reason” to fight, but the battle went on. This created a kind of stress, an intellectual shock for our political elite, our army, and secret services, because Russian liberals tried to become part of the global world. They didn’t care about sovereignty, tradition, or conserving Russian values, everything of which was for them negative. But the real state, the Russian Deep State, had to react somehow.

The collapse of the communist system disarmed Moscow ideologically, as they could not explain or understand foreign policy. The foreign policy and military strategy of the USSR was based on the concept of confrontation between the socialist camp, the East, and the capitalist camp. The reason of this confrontation was seen precisely only in ideological terms. Outside and beside ideology, there should have been no conflict, yet conflict still continued. When this ideological vision was lost, Russia unilaterally disarmed itself and pretended to be as capitalist, democratic, and liberal as the West. There was no ideological reason to continue opposition. But the West continued to expand NATO to the East, swallowing Eastern Europe and strangling Russia. That created a cognitive dissonance. Something didn’t fit. There was a kind of schizophrenia in the state and society. Why were they against us, when we were no longer against them? We were not defeated in this situation, so it was our free will to stop the confrontation, but they continued the confrontation. Why? Where is the rational, logical reason?

It was precisely at this moment, in the beginning of the 1990’s, that geopolitics was discovered in Russia in the Military Academy of the General Staff and elsewhere. This was done with our help, because I was not a communist; I was very interested in other philosophies, and I discovered conservative values before the fall of communism, being a little bit at a distance from the ruling ideology. Very few people were prepared to respond. I established in the late 1980’s relations with some conservative and traditionalist circles in Europe who were very interested in Carl Schmitt and geopolitics. And when there was the fall of communism, we tried to explain to our generals, our military men, what happened from a geopolitical point of view. That was the only reason: to give a rational explanation of what was happening now, after the end of the Soviet Union, outside of communist ideology, to answer how we can explain this confrontation, opposition, and fight outside of ideology. The liberals in the government and society rejected this approach, because they continued to follow the rules of the West. Geopolitics was a “forbidden” or “pseudo-science” - Soros came to Russia in order to say that “geopolitics is all wrong” - meaning for Russia and for China, but not for them.

Little by little, we have succeeded in establishing geopolitics as the main strategic approach of the Russian Federation. Through the deep state, through military circles, through patriots, we have succeeded in making geopolitics very famous, known, and now in all universities and institutions in Russia, in both the humanitarian and social sciences, they teach geopolitics. That is how geopolitics became the main theoretical field in Russia.

In Shanghai in China, a few months ago in June, I met Dr. Feng Shaolei (director of Centre for Russian Studies in East China Normal University) at a press conference with Prof. Zhang Weiwei organized by guancha.cn, and he said that he had just returned from Russia’s Valdai Club and met Mr. Putin. This Chinese professor asked Mr. Putin: “What is the theoretical basis on which you make your political orientations?” Putin responded: “Geopolitics, not ideology.”

We started in the 1990’s, but there has been a serious paradigm shift with Putin. Now, geopolitics is the prevailing attitude in Russian strategy. That is how the Russian geopolitical school was established, as a continuation of Haushofer’s ideas, except for the role of the subject in geopolitical dualism, as in the case of Russia we had much more of a foundation and many more reasons for this: since Germany was the European Heartland, we are the absolute absolute Heartland, according to Mackinder. This is the Eurasia concept, born at that moment. This was the acceptance of the title, rank, or position of a subject on the geopolitical map. This was the acceptance of the relevance of classical Anglo-Saxon geopolitics and the basic dualism of Mackinder. With the affirmation of Heartland as a subject, Behemoth becomes conscious in that moment. There was the identification of the US and NATO as antagonistic forces, but recognized as subjects too - that is a difference. In Eurasian geopolitics, we recognize that Sea Power is a subject. There is not only a one-subject/one-object game. There are two subjects. We are against them, but we recognize them as a formal enemy in accordance with Carl Schmitt’s theory. They constitute themselves as such for us and help us to understand ourselves, as in the pair of Carl Schmitt’s concept of Friend and Enemy. We consider that they have the right to exist, but they have no right to rule us and the space that we consider naturally ours.

All of Putin’s politics is about that: the restoration of sovereignty, getting them out of our space, not letting them impose on us their principles or their Sea Power strategy, because we have a different identity. Taking into account the German Continental tradition, which was ambivalent and not so much really Continental and taking into account the metaphysical depth in Carl Schmitt was very important in the creation of the Russian school of geopolitics. Then we discovered that, already in the beginning of the 20th century, in the White Russian emigration, there was a movement that was called the Eurasianist movement and, to my astonishment, one of the founders of this movement, Petr Savitsky, who was a geographer, had read Mackinder and had already made the first efforts to propose the understanding of Russia as Eurasia, as Heartland, against Sea Power. This was a continuation of the Slavophile tradition in Russian culture.

Starting from the Anglo-Saxons and passing through the Germans, we have discovered in our own proper Russian tradition a marginal [affirmation of such]. Before, the Eurasianists were almost unknown, because they were anti-communist, and therefore were not known in Soviet Russia, but they were in favor of the Soviet Union against the West - they were marginalized in the emigration because they were not in favor of the West, and were anti-Nazi and anti-CIA, while the other part of the White emigration collaborated with Western special services in order to fight communism. The Eurasianists were a small minority in this emigration because they were in favor of Soviet communism for geopolitical reasons, because of hatred for the West, but they were not communists. Thus we re-founded the Eurasianist movement, because we discovered that there was someone like us who precisely predicted earlier that there will be a moment when communism will fall as an anti-Russian ideology - too materialistic and without an understanding of identity, tradition, spiritual traditions, the Christian tradition, having been destroying all that - and after that should come the Eurasianists, in order to continue the fight for independence and sovereignty, which was a positive side of the communist regime, including in Stalin’s opposition to the West and Soviet opposition to the West in general. We discovered our own Eurasianists from a very special way or path, from the Anglo-Saxons to the Germans to our proper roots.

While the first program on this was published in 1997 in my Foundations of Geopolitics, the first texts were published just after the fall of communism, in 1991 in a magazine called Den’ [“Day”], whose editor in chief was Alexander Prokhanov, now the president of the Izborsky Club, one of the main conservative think tanks [in Russia]. That was precisely when we started the promotion of Eurasianism, and the creation of the Eurasian movement came 10 years afterwards. The beginning of the creation of the Russian geopolitical school and Eurasian attitude started just after the fall of the Soviet Union, and that is precisely what the first Eurasianists thought would happen.

Now for the counter-strategy of the Eurasian geopolitics. If there is one subject, then there is a second one. There is Sea Power and there is Land Power. There is the old Rimland. There is the fight for control, because Sea Power wants to make this zone broader, and Land Power seeks to make this zone smaller. What is important is that now Russia is not the Soviet Union; it is not one of two poles. We have no capacity, no possibility, no resources, and no ideology to impose ourselves as the main ruling power of Rimland. That is a very important shift from bipolarity in the Sea Power-Land Power dualism to multipolarity.

We can make this Rimland safe for us without colonizing it, which is just impossible, by creating friends, an alliance, and helping in a symmetric way different powers to grow and become more and more independent from Sea Power. Now this explains why we have no real desire or capacity to follow the Tsarist or Soviet strategy of more or less bipolarity, and we have no ideology. There is no ideology in Russia - Russia is pragmatic, it is a little bit liberal, but not liberal like in Sea Power, a little bit nationalist, patriotic, and conservative, with a partly traditional society under the growing role of the Orthodox Church and a growing feeling of identity. But that is not ideology: we could not go to Iran and say “accept our ideology”, for we have nothing of the sort, and we could not go to Turkey, India, or China with tanks, and we cannot export anything of the sort.

But how, in that situation, can we save ourselves from Sea Power? By way of friendship, accepting the Other as they are, accepting their identities. For us is not so much important for Rimland to be pro-Russia or not - most important is that Rimland should not be pro-American. That is the main question. You could hate us, but if you don’t like the Americans, if you are not under their control, and if you are independent, that’s enough. We can support you, while being completely indifferent. We don’t suggest any ideology, direct rule, or domination, because we don’t have the power to do so. Compared to the Soviet Union or Tsarist Empire, our weakness is our main privilege. We are playing with our weakness. When the Turks see us, they understand that in such a situation we could not make war against them - we have no idea, no reason for such. If they are Muslims, and we are Christians with many Muslims inside of Russia, we have no problem with them if they do not attack us. When the peoples of our ancient enemies, like Turks or Persians, start to understand that Russia does not represent a threat anymore, they start to see in us a kind of possible ally. And little by little, this alliance is growing. In Syria we have organized such an alliance in a very practical way. This is the fight for the Rimland. Iran is totally anti-Sea Power and Turkey is becoming such. The more anti-Sea Power that Erdogan is, the more he is a friend of Putin. That is all the geopolitics that are actual now.

The main shift was precisely with Putin, who has accepted this vision. Yeltsin and the liberals rejected this vision. Why? Because they were tools of the West, and nothing else. They were not Russian politicians properly speaking, but Western politicians trying to dissolve Land Power. They are called the Fifth Column in Russia, as they tried to open the door for the enemy and let him in.

The new Heartland strategy cannot be bipolar anymore. It can only be multipolar, with all sincerity. This is not a kind of “hidden” version of old bipolarity, as such is impossible in the present situation. We cannot let Sea Power rule Land Power. That is essential, in the end. We can make this possible only with the help of other poles.

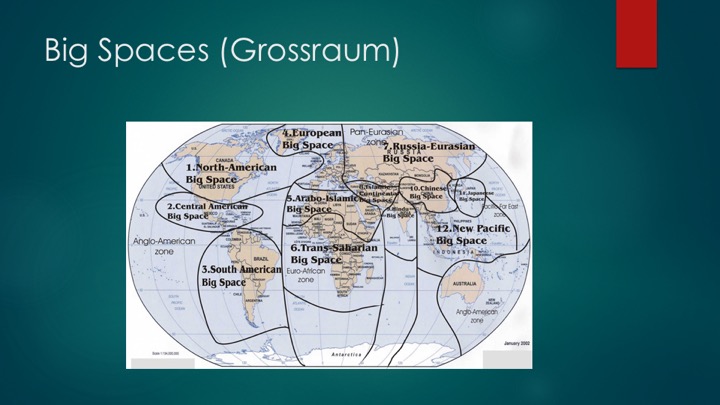

At the same time, we have discovered the ideas of another Schmittean concept: Big Spaces. Big Spaces are more or less “poles”, but some Big Spaces are already fully established, some are in the process of being created, while some are in the process of decline.

Here is a map where there are the different Big Spaces which we have started to deal with approximately, in a practical sense. Of course, they could be arranged differently. If some are too weak, they can become part of the stronger ones. This is a very dynamic situation, not something fixed. Nevertheless, this map representing Big Spaces is the same as Huntington’s map of civilizations. These Big Spaces roughly coincide with “civilizations.” Hence the concept that a pole in the multipolar world should not be a country or power in the ancient understanding, but new players, who should be civilizations. The forms or strategic expressions of these civilizations are Big Spaces. The content and sense of these are civilizations. We see in these Big Spaces, in this concept, the main power lines of Russian politics.

What we want from the European Big Space is one thing: for NATO to get out, and to create with us a kind of Eurasian strategy. For that reason we are helping everybody who shares with us this idea and who is against Atlanticism - Left or Right, it doesn’t matter. Hence the support for populists. That is our counter-strategy. Putin affirms the concept of Greater Eurasia-Greater Europe from Lisbon to Vladivostok. That is the idea towards Europe. But that is not all: we need something to propose to the Islamic continental Space, including Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and we cannot impose on them our vision, Christianize them, or impose some idea - nobody wants that. We should accept them as Islamic and try to establish a strategic alliance with them. The same goes for the Arabo-Islamic space, the same with India, the same with China, the same with Japan. I am speaking of all possibilities.

Why does Putin want to give the Kuril Islands to Japan? In order to try to transform Japan from an enemy, under the control of the West, into a neutral power. Maybe it will not happen, but what is important is the logic I am trying to explain, of how the logic of Big Spaces is reflected in Russia’s concrete foreign policy. That is pure geopolitics. We are coming into the Trans-Saharan space as well together with the Chinese. We are trying to help some forces in the South American Big Space, in the Central American Big Space, and if the North American Big Space will be limited by this region, they can be our friends. Why not? They are very interesting guys, when they are put in their natural civilizational borders. When Trump began his campaign, he promised to stop interventions, to take American forces back from all around the world and to concentrate on inner problems. We didn’t believe him, but we applauded him. That is absolutely the right way to Make America Great Again.

We are not alone in this world with our plans.

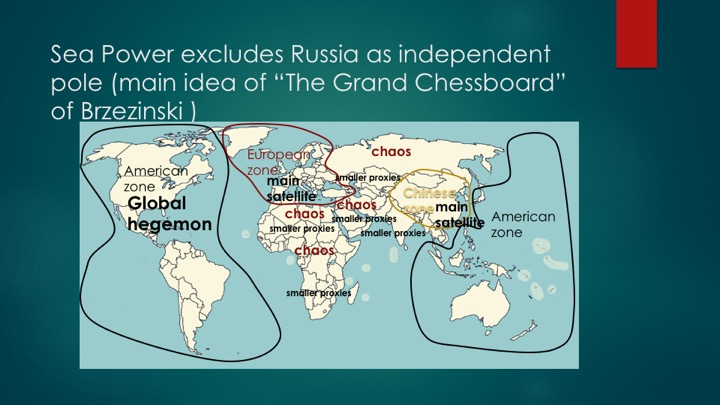

There is another map, much more terrifying I would say, which is what the globalists of Sea Power want to do. This is a completely different vision. We are shifting from the standpoint of Land Power to that of Sea Power. What they propose is a completely different situation. They cannot ignore the Chinese anymore, so their idea is to include China in their future plan, proposed as “G2” by Hillary Clinton when she came here and was accepted very politely, but without much success. China is thinking about what to do in this situation while dealing with all the geopolitical possibilities, not ready to accept anything too early or too easily. But the globalists are ready to include China as a capitalist, liberal Sea Power, with Shanghai, this coastal area of prosperity, but maybe without the inner part of Xinjiang, Tibet, and continental China with its peasantry and traditional society, that is the main basis of the Communist Party that cannot be accepted in the Americans’ plan. So they will bother to change the situation, to push more liberalization, capitalization, and “human rights” here; that is the work of the network of Soros, the Fifth Column, and the Sixth Column, as everywhere. China is to be the main satellite in this concept, with certain conditions. The other main satellite is the European zone. This is more or less the wishful thinking of the American political elite, to see the world as such. They have already sown chaos in North Africa, and in the Middle East, such as by creating a Kurdish state, trying to diminish the influence of Turkey, Iran, Syria, and destroying everything, but not creating anything instead.

Chaos strategy does not suggest creation or a new political system or order instead of the destroyed political systems. It is manipulated, moderated chaos - a new way of strategic thinking. If we carefully read Brzezinski’s book, The Grand Chessboard, it is written that they need a balkanized Eurasia, to transform it into a zone of permanent conflict between different groups - between Muslims, between ethnic groups, between Russians and Ukrainians, for example. This was Brzezinski’s idea. Chaos is already sown in Africa, so they don’t have to bother too much about that, while now the Russians and Chinese are coming here to bring another order, maybe not the best, but not bloody chaos as is the current situation. There are different points - smaller proxies, partly India, partly some pro-Western little states, and Israel for aggravating and make the chaos bigger. Smaller proxies, like Ukraine for example, are not allies in this concept, but just points in order to make chaos bigger. That is more or less how they understand the situation.

That is why the concept of peace and independent poles is absent in any of their plans for the future. It is a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. They don’t let even a quadripolar system have any appeal; they cannot let it happen, even theoretically, because they know the power of words. They destroy any mention of quadripolarity. All the books of American experts, strategists, “fortune-tellers” as a I like to say, and political analysts try to destroy and eliminate these poles. There should be only chaos, and by having chaos, they can create a world in which they can still have global power and rule the world. They will not properly rule Eurasia with a better government - they don’t need Russia at all; they blame Russia and Putin not because they don’t like Putin, but because they won’t let Russia be. This is ontological. It is Sea Power vs. Land Power. Nothing personal. Putin could follow some concrete agreement with them, but they don’t regard Russia as a subject, only chaos.

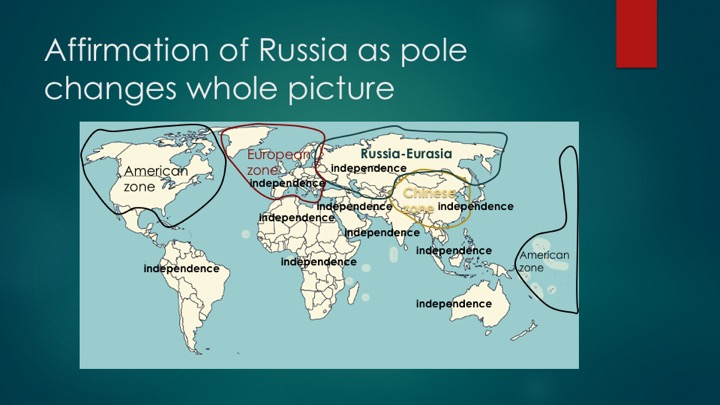

But if we recognize the pole of Eurasia, we see a completely different situation. First of all, the European and Chinese zones immediately become independent. They lose their certain dependence on the West, while not exchanging this dependence for dependence on Russia. In Japan, with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, I have tried to explain this to the Japanese, but they said: “You want to establish Eurasian rule instead of American rule. When the Americans go out, you will come.” I said: “You have not understood the main idea.” If they are here, there will be only chaos. China and Europe will be dependent on the West, whether recognized as “multilateral allies” or something else, but with Russia here, you will be independent - from them, but from us as well, because we cannot threaten you. Everybody else obtains independence.

Independence is not happiness or a happy end. It is a challenge, because you should be strong and have an identity. Independence is the burden of the multipolar world. It is not a gift. It is a chance to affirm identity. For the partisans of identity, culture, and the spirit of civilizations, it is a gift, but for governments, it is a huge burden, because you are responsible for organizing and managing without ready-made solutions. Now, in the unipolar world, they suggest you should follow their rule, do this and that, and everything will be alright - maybe not now, perhaps you should pass through some shock therapy, and so on. But independence is real freedom and a real chance, a chance that is open. History does not end there. History is open.

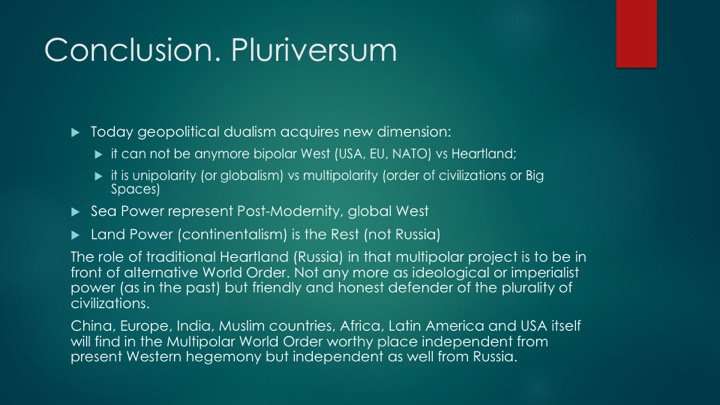

Today, geopolitical dualism acquires a new dimension. It is not anymore bipolar as in the West vs. Heartland. It is unipolarity and globalism vs. multipolarity, the order of civilizations or Big Spaces.

Can we identify the Eurasian project with the famous Chinese win-win strategy? Certainly not. Because Sea Power is going to lose its domination and leading role, as was the case in the unipolar moment. They had the chance after the fall of communism to have global domination and rule. They enjoyed this chance, this possibility, over 10 years. But with 9/11 and Putin’s coming to power, their domination has been limited. So why not a win-win? Because someone has to pay for multipolarity. If there is multipolarity, someone has to lose. Will Continental Heartland pay for multipolarity? Or will there be the global domination of the West, that will lose? This is a win-lose strategy that is an open, continental fight in which there is no neutral solution.

One solution is multipolarity. On the other side is unipolarity and globalization. That is not a win-win. But at the same time, the exit, the success, or the end of all this is not granted. It is open history. The end of history has ended. I spoke about this with Fukuyama in Washington, and he has since recognized that he was too much in a hurry to declare that the end of history has already happened. Now the end of history is finished. There is no more end of history. History is here, with all the possibilities, dangers, all the risks, all the open ends, and moving ends within the context of open history. In history, there is no win-win. Someone should lose. The conclusion, according to the Eurasianist world-vision, is that Sea Power should lost this time, and we should win.

Transcript prepared by Jafe Arnold (Eurasianist archive )

Bibliography

Abe I. Chiseigaku nyumon. Tokyo: Kokon-Shoin, 1933.

Achcar G. Greater Middle East: the US Plan – www. mondediplo.co. 2004. [Электронный ресурс] URL: http://mondediplo.com/2004/04/04world (дата обращения 03.09.2010).

Agnew J. Geopolitics: Re-Visioning World Politics. Londres: Routledge, 1998.

AgnewJ., Mitchell K. & O’Thuatail G.(eds.) A Companion to Political Geography. London: Blackwell, 2002.

Al-Rodhan N.R.F. Neo-statecraft and meta-geopolitics. Berlin: Lit Verlag, 2009.

Aldrich R. J. The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence. Duckworth, 2006.

Ambrosio Th. Challenging America global Preeminence: Russian Quest for Multipolarity. Chippenheim, Wiltshire: Anthony Rose, 2005.

Amin S. Eurocentrism. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010.

Amin S. The Liberal Virus. London: Pluto Press, 2005.

Amin S. Transforming the revolution: social movements and the world-system. Delhi: Aakar Books, 2006.

Ancel J. Géopolitique. Paris: Bibliothèque d'Histoire et de Politique, 1936.

Ancel J. Geographies des frontiers. Paris: Gallimard, 1938.

Aras B. The new geopolitics of Eurasia and Turkey's position. London: Frank Cass, 2002.

Armstrong D. Drafting a plan for global dominance // Harper's Magazine. October 2002.

Attali J. Lignes d'horizon. Paris:Fayard, 1990.

Axelos K. Vers la pensée planétaire. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1964.

Barnett T. P. M. Great Powers: America and the World after Bush. New York: Putnam Publishing Group, 2009.

Barnett T. P. M. The Pentagon's New Map. New York: Putnam Publishing Group, 2004.

Beales A. C. F. The history of peace; a short account of the organised movements for international peace. New York: Garland Pub., 1971.

Beck U. Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne. Frankfurt a.M.:Suhrkamp, 1986.

Behar P. Une géopolitique pour l'Europe, vers une nouvelle Eurasie. P.: Editions Desjonquères, 1992.

Benoist A. de. Europe, Tiers Monde Meme Combat. P.:Laffont, 1986.

Benoist A. de. L'idée d'Empire/ Actes du XXIVe colloque national du GRECE. Nation et Empire. Histoire et concept. Paris: GRECE 1991.

Bhagwati J. N. Free Trade Today. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Bhagwati J. N. In Defense of Globalization. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bowman I. Geography in relation to the social sciences. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1934.

Bowman I. Geography vs. Geopolitics. New York: American geographical society, 1942.

Bowman I. International Relations. Chicago: American Library Association, 1930.

Bowman I. The new world: problems in political geography. Chicago: World Book Company, 1928.

Braudel F. (dir.) La Méditerranée. L’espace et les hommes. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques, 1977.

Braudel F. Civilisation matérielle, économie et capitalisme (XVe-XVIIIe siècles). 3 volumes. Paris, Armand Colin, 1979.

Brechtefeld J. Mitteleuropa and German politics. New York, 1996.

BRICs and beyond. Goldman Sachs Global Economics Group. NY, 2007.

Bruhnes J. Geographie humaine. Paris: Michelet, 1910.

Brzezinski Z. America and the World: Conversations on the Future of American Foreign Policy. New York: Basic Books, 2008.

Brzezinski Z. Between Two Ages : America's Role in the Technetronic Era. New York: Viking Press, 1970.

Brzezinski Z. Game Plan: A Geostrategic Framework for the Conduct of the U.S.-Soviet Contest. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1986.

Brzezinski Z. Grand Failure: The Birth and Death of Communism in the Twentieth Century. New York: Charles Scribner's Son, 1989.

Brzezinski Z. Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977-1981. New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux,1983.

Brzezinski Z. The Choice: Global Domination or Global Leadership, New York: Basic Books, 2004.

Brzezinski Z. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Brzezinski Z. Second Chance: Three Presidents and the Crisis of American Superpower. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

Brzezinski Z. Soviet Bloc: Unity and Conflict, N.Y. Harvard University Press, 1967.

Burnham J. The Struggle for the World. New York: The John Day Company, Inc, 1947.

Canagarajah A. S. A geopolitics of academic writing. Pitssburgh: University of Pitssburgh Press, 2002.

Chauprade A., Thual F. Dictionnaire de géopolitique. Paris: Ellipses, 1999.

Chauprade A. Géopolitique - Constantes et changements dans l'histoire. Paris: Ellipses, 2007.

Chauprade A. Introduction à l'analyse géopolitique. Paris: Ellipses, 1999.

Chauprade A. Les Balkans, la Guerre du Kosovo (en collaboration). Paris/Lausanne: L'Âge d'Homme, 2000.

Chauprade A. Géopolitique des États-Unis (culture, intérêts, stratégies). Paris: Ellipses, 2003.

Chauprade A. Une nouvelle géopolitique du pétrole en Afrique //Chronique du choc des civilizations. Editions Chronique. Janvier, 2009.

Cheradame A. L'Allemagne, дa France et la question de l'Autriche. P.:Plon, 1902.

Chomsky N. The Cold War and the Superpowers// Monthly Review. Vol. 33. № 6. November 1981. С. 1–10.

Chomsky N. Profit over people: neoliberalism and global order. New York: Seven Stories Press, 1999.

Chomsky N. Hegemony or survival: America's quest for global dominance. New York: Penguin, 2007.

Cohen S.B. Geography and Politics in a World Divided. New York: Praeger, 1963.

Cohen S.B. Geopolitics of World System. NY: Rowman&Littlefield publishers, 2002.

Cohn N. The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages. London; New York: Oxford University Press, 1957.

Coudenhove-Kalergi R. Paneuropa. Wien, 1923.

Coutau-Bégarie H. 2030, la fin de la mondialisation? P.: Artege, 2009.

Coutau-Bégarie H. Géostratégie du Pacifique. P.: Economica, 2001.

Coutau-Bégarie H. La Lutte pour l’empire de la mer. P.: Economica, 1999.

Coutau-Bégarie H. Marins et océans. 2 v. P.: Economica, 1999.

Coutau-Bégarie H. Pensée stratégique et humanisme. P.: Economica, 2000.

Crocker D. A. Ethics of Global Development: Agency, Capability, and Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Cunningham L. A. From Random Walks to Chaotic Crashes: The Linear Genealogy of the Efficient Capital Market Hypothesis//George Washington Law Review. 1994. Vol. 62

Daly H. E. Globalization and Its Discontents// Philosophy and Public Policy Quarterly. 2001. 21, 2/3.

Daly H. E. Globalization’s Major Inconsistencies//Philosophy and Public Policy Quarterly. 2003. 23, 4.

Debrix F., Lacy M. The geopolitics of American insecurity: terror, power and foreign policy. Abingdon: Routlede, 2009.

Desan W. The Planetary Man, Vol. 1: A Noetic Prelude to a United World. Washington,DC: Georgetown University Press, 1961.

Dodds K. Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Dodds K. Geopolitics in a changing world. London: Prentice Hall, 2000.

Dodds K. Global geopolitics: a critical introduction. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd, 2005.

Dolman E. C. Geostrategy in the Space Age: An Astropolitical Analysis/ Gray Colin S., Sloan G. (ed.) Geopolitics, Geography and Strategy. London: Frank Cass, 2003.

Dorrien G. Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Douguine A. Le prophete de l’eurasisme. Paris:Avatar, 2006; Idem. La grande guerre des continents. Paris:Avatar, 2006.

Douhet G. Command of the Air. New York : Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1942.

Dughin A. Continente Russia. Parma: All'isegno di Veltro, 1992.

Dughin A. Eurasia. La Rivoluzione Conservatrice in Russis. Roma, 2005.

Dughin A. Fundamentele geopoliticii. Bucarest.:Andersen Media, 2010.

Dugin A. A grande guerra dos continentos. Lisboa, 2010.

Dugin A. Geopolitikis safudzvlebi. Rusetis geopolitikis momavali. Tbilisi: Gamomgtsemloba, 1999.

Dugin A. Misyonin avrasyagilik Nursultanain Nazarbaevin. Ankara, 2006.

Dugin A. Moska-Ankara aksiaynin. Istambul: Kaynak, 2007.

Dugin A. Osnove geopolitike. Beograd, 2004.

Dugin A. Rusia. Misterio de Eurasia. Madrid:Grupo Libro 88, 1992.

Dugin A.Rus jeopolitigi avrasyaci yaklasim. Ankara, 2003.

Dugin A. Seminal writings. 3 v. L., 2000.

Dugin I. Feisaliny jeopolitidgi. Beyruth, 2004.

Dyer G. Climate War. Montreal: Random House of Canada, 2009.

Ebeling F. Karl Haushofer und die deustche Geopolitik 1919-1945. unpubl. diss. Hanover, 1992.

Engdahl F. Full Spectrum Dominance: Totalitarian Democracy in the New World Order. Boxboro, MA: Third Millennium Press, 2009.

Engdahl F. Century of War: Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order. London: Pluto 2004.

Foster J. B. Imperial America’ and War// Monthly Review. 2003. May.Vol. 55.№. 1. С. 1–10

Fouere Y. Contre les etats: regions d'Europe P.:Presse d'Europe, 1971.

Fouere Y. Europe aux cents drapeaux. P.:Presse d'Europe, 1968.

Foucher M. Fronts et Frontières, un tour du monde géopolitique. P.: Fayard, 1988; Idem. L'invention des Frontières. P.: FEDN, 1986.

Foucher M., Dorion H. (dir.) Frontière(s), scènes de vie entre les lignes. P.: Glénat, 2006.

Friedman T. L. The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization .New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999.

Friedman T. L. The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005

Fukuyama F. 2004. State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century. New York: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Gallois. P.-M. Géopolitique, les voies de la puissance. P.:Plon, 1990.

Gill S. American Hegemony and the Trilateral Commission. Boston: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Gray C.S. The geopolitics of the nuclear era: heartland, rimlands, and the technological revolution. New York: Crane Russak & Co, 1977.

Gray C.S., Sloan G. Geopolitics, geography and strategy. London: Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 1999.

Gray C.S. Strategy and History: Essays on Theory and Practice. Abingdon, UK:Routledge, 2006.

Gray C.S. Strategy for Chaos: Revolutions in Military Affairs and Other Evidence of History. London: Frank Cass, 2002

Gray C.S. The Geopolitics of Super Power. Lexington, KY:University Press of Kentucky, 1988.

Gray C.S. The Leverage of Sea Power:The Strategic Advantage of Navies in War. New York: The Free Press, 1992.

Gray C.S. War, Peace, and Victory:Strategy and Statecraft for the Next Century. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Greenberg A. S. Manifest Manhood and the Antebellum American Empire. Cambridge U. Press, 2005. .

Grossouvre de H. Paris, Berlin, Moscow: Prospects for Eurasian cooperaion // World Affairs. Vol 8. Jan–Mar 2004. №1.

Haass R. The Age of Non-polarity: What will follow US Dominance?//Foreign Affairs. 2008. 87 (3). p. 44-56.

Hackmann R. Globalization: myth, miracle, mirage. Lanham: University Press of America, 2005.

Haushofer K. Bausteine zur Geopolitik. Heidelberg: K. Vowickel, 1924.

Haushofer K. Dai Nihon. Betrachtungen uber Gross-Japans Wehrschaft und Zukunft. Berlin:E.S.Mittler, 1913.

Haushofer K. Das japanische Reich in seiner geographischen Entwicklung.Wien, Seidel, 1921.

Haushofer K. Das Reich: Grossdeutches Werden im Abendland. Berlin: Karl Habel Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1943.

Haushofer K. Der Kontinentalblock. München : Eher, 1941.

Haushofer K. Geopolitik der Pan-Ideen. Berlin: Zentral-Verlag, 1931.

Haushofer K. Geopolitik des Pazifischen Ozeans: Studien über die Wechselbeziehungen zwischen Geographie und Geschichte. Mit sechzehn Karten und Tafeln. Heidelberg: K. Vowickel, 1924.

Haushofer K. Grenzen in ihrer geographischen und politischen bedeutung. Heidelberg: K. Vowinckel, 1939.

Haushofer K. Japan baut sein reich. Berlin: Zeitgeschichte Verlag, 1941.

Haushofer K. Weltmeere und Weltmachte. Berlin: Zeitgeschichte Verlag, 1941.

Haushofer K. Weltpolitik von heute. Berlin: Zeitgeschichte Verlag, 1936.

Held D., McGrew A. Globalization Theory: Approaches and Controversies. Polity, 2007.

Held D., McGrew A., Goldblatt D., Perraton J. Global Transformations. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Heim M. The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality. Oxford, 1993.

Hesse F. Das gesetz der wachsende Raume/Zeitschrift fuer Geopolitik. 1924. 1 Jg. С. 1-10.

Hettner A. Die Geographie, ihre Geschichte, ihr Wesen und ihre Methoden. Breslau: Ferdinand Hirt, 1927.

Hettner А. Die Geographie, ihre Geschichte, ihr Wesen und ihre Methoden. Breslau: Ferdinand Hirt, 1927.

Higgott R. Multi-Polarity and Trans-Atlantic Relations: Normative Aspirations and Practical Limits of EU Foreign Policy. – www.garnet-eu.org. 2010. [Электронный ресурс] URL: http://www.garnet-eu.org/fileadmin/documents/working_papers/7610.pdf (дата обращения 28.08.2010).

Hiro D. After Empire: The Birth of a Multipolar World. Yale: Nation Books, 2009.

Hirst P., Thompson G. Globalization in Question: The International Economy and the Possibilities of Governance.Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996.

Hock D. Birth of the Chaordic Age. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 1999.

Holbrooke R. America, A European Power.//Foreign Affairs. March/April, 1995.

Horowitz D. From Yalta to Vietnam: American Foreign Policy in the Cold War. N.Y., 1967.

Hugon P. African geopolitics. Princeton, NJ: Markus Weiner Publishers, 2008.

Hulsman J. Cherry-Picking: Preventing the Emergence of a PermanentFranco-German-Russian Alliance. – www.heritage.org. 2003. [Электронный ресурс] URL: http://www.heritage.org/Research/Reports/2003/08/Cherry-Picking-Preventi... (дата обращения 03.09.2010).

Huntington S. P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Iimot N. Iwayuru chiseigaku no gainen/Chirigaku Hyoron, 1928.

Immerman R. H. John Foster Dulles: Piety, Pragmatism, and Power in U.S. Foreign Policy. New York: SR Books, 1998.

Johnson R. Spying for Empire: The Great Game in Central and South Asia, 1757-1947. London: Greenhill, 2006.

Jones St. B. Boundary-making: A Handbook for Statesmen, Treaty Editors and Boundary Commissioners. Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Division of International Law, 1945.

Jones St. B. Unified Field Theory of political Geography//Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1954. June. V.XLIV n.2 С. 111-123.

Joyaux F. Géopolitique de l'Extrême-Orient, Espaces et politiques. Bruxelles: Éditions Complexe, 1991.

Kagan R. Dangerous nation. New York: Vintage, 2007.

Kagan R. Of paradise and power: America and Europe in the new world order. New York: Vintage, 2004.

Kagan R. The Return of History and the End of Dreams. New York: Vintage, 2009.

Kagan R., Kristol W. Present dangers: crisis and opportunity in American foreign and defense policy. New York: Encounter Books, 2000.

Kagan R. The Case for a League of Democracies// Financial Times. 2008. May 13.

Kaplan R.D. Imperial Grunts: On the Ground with the American Military, from Mongolia to the Philippines to Iraq and Beyond. NY: Vintage, 2006.

Kaplan R.D. The coming Anarchy: Shaterring deram of the Cold War. NY: Random House, 2000.

Katz M. Primakov Redux. Putin’s Pursuit of «Multipolarism» in Asia//Demokratizatsya. 2006. vol.14 № 4. C.144-152.

Kennan G. F. The Sources of Soviet Conduct//Foreign Affairs, July 1947.

Kennan G. F. Russia, the Atom, and the West. New York: Harper, 1958.

Kennedy P. The Rise and Fall of Great Powers. New York: Random House, 1987.

Keohane R., Nye J.S.Jr. Power and Interdependance in the Information Age//Foreign Affairs. 1988. 77/5 (Sept.Oct.). С. 81-94.

Khanna P. Der Kampf um die zweite Welt – Imperien und Einfluss in der neuen Weltordnung. Berlin: Berlin Verlag, 2008.

Kilinc T. Turkey Should Leave the NATO – www.turkishweekly.net. 2007. [Электронный ресурс] URL: http://www.turkishweekly.net/news/45366/tuncer-kilinc-%F4c%DDturkey-shou... (дата обращения 03.09.2010).

Kincaid C. McCain, Soros, and the New «Global Order» – www.aim.org. 2008. [Электронный ресурс]URL: http://www.aim.org/aim-column/mccain-soros-and-the-new-global-order/ (дата обращения 20.09.2010.)

King A., Schneider B. The First Global Revolution: A Report by the Council of Rome. London: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

Kirk W. Historical geography and the concept of behavioral environnement//Indian geographical journal& Silver Juvelee volume. 1952. С.152-160.

Kissinger H. Crisis: The Anatomy of Two Major Foreign Policy Crises. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Kissinger H. Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994.

Kissinger H. Does America need a foreign policy?: toward a diplomacy for the 21st century. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002.

Kissinger H. White House Years. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1979.

Klare М. Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: The New Geopolitics of Energy. New York: Henry Holt & Company Incorporated, 2008.

Krasner S. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Krauthammer Ch. The Unipolar Moment// Foreign Affairs. 1990/1991 Winter. Vol. 70, No 1. С. 23-33.

Kristol I. Neoconservatism: the autobiography of an idea. Lanham: Ivan R. Dee, 1999.

Lacoste Y. Dictionnaire geopoliqiue. Paris: Flammarion, 1986.

Lacoste Y. Geopolitique: la longue histoire d'aujourd'hui, Paris: Larousse, 2006.

Lacoste Y. Géopolitique de la Méditerranée. Paris: Colin, 2006.

Lacoste Y. La Géopolitique. Paris: Centre national de documentation pédagogique, 1990.

Larson A. Geopolitics of oil and natural gas // Economic Perspectives vol. 9. №2. May 2004.

Lash S., Featherstone M. (eds.) Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World. London: Sage, 1999.

Lash S., Szerszynski B., Wynne B. (eds.) Risk, Environment and Modernity. London: Sage (TCS), 1996.

Lash S., Featherstone M., Szerszynski B., Wynne B. Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World. London: Sage, 1999.

Lash S., Lury C. Global Culture Industry: The Mediation of Things. Cambridge: Polity, 2005.

Laurant J.-P. Le Regard ésotérique. Paris: Bayard, 2001.

Layne C. The peace of illusions: American grand strategy from 1940 to the present. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006.

Le Billon P. Geopolitics of resource wars: resource dependence, governance and violence. Abingdon: Frank Cass, 2005.

Lechner F. J., Boli J. The Globalization Reader. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

Leech H. J. The public letters of the Right Hon. John Bright. London: Low, Marston & Co., 1895.

Lefebvre H. La production de l'espace. Paris: Anthropos, 1974.

Liu Henry C. K. Obama, change and China.Brzezinski's G-2 grand strategy – Asian Times. 2009.22.04. [Электронный ресурс] URL: http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China_Business/KD22Cb02.html (дата обращения 24.08.2010).

Lohausen H.J. von. Denken in Völkern. Die Kraft von Sprache und Raum in der Kultur- und Weltgeschichte. Graz: Stocker 2001.

Lohausen H.J. von. Ein Schritt zum Atlantik: Die strategische Bedeutung d. Ostverträge. Wien: Österr. Landsmannschaft, 1973.

Lohausen H.J. von. Les empires et la puissance: la géopolitique aujourd'hui. Paris: Le Labyrinthe, 1996.

Lohausen H.J. von. Denken in Kontinenten. Berg am See: Kurt Vowinckel Verlag, 1978.

Lohausen H.J. von. Reiten für Russland: Gespräche im Sattel. Graz: Stocker, 1998.

Lohausen H.J. von. Zur Lage der Nation. Krefeld: Sinus-Verlag, 1982.

Lonsdale D. J. Informational power: strategy, geopolitics and the fifth dimension/ Gray Colin S., Sloan G. (ed.) Geopolitics, Geography and Strategy. London: Frank Cass, 2003.

Lorenz E. The Essence of Chaos. Washington: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Lorot P. Guellec J. (ed.) Planète Océane. L’essentiel de la mer. P.: Choiseul, 2006.

Lorot P., Thual F. La Géopolitique. P.: Montchretien, 1997.

Luttwak E. Sea Power in the Mediterranean: Political Utility and Military Constraints. California, 1979.

Luttwak E. Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace. Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1987.

Luttwak E. The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2009.

Luttwak E. The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire from the First Century AD to the Third. Baltimore, 1976.

Luttwak E. The Political Uses of Sea Power. Baltimore, 1974.

Luttwak E. Coup d'État: A Practical Handbook. London, 1968.

Luttwak E. From Geopolitics to'Geoeconomics. Logic of Conflict, Grammar of Commerce//The National Interest.1990.Summer. С. 17—23.

Luttwak E. The Endangered American Dream: How To Stop the United States from Being a Third World Country and How To Win the Geo-Economic Struggle for Industrial Supremacy. New York, 1993.

Luttwak E. Turbo-Capitalism: Winners and Losers in the Global Economy. New York, 1999.

Mackinder H. J. Britain and the British Seas. Charleston: BiblioLife, 2010.

Mackinder H. J. Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1996.

Mackinder H.J. On the Scope and Methods of Geography//Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography. 1887. New Monthly Series, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Mar.).

Mackinder H. J. Situation in South Russia 21 Jan. 1920//Documents on foreign policy 1919-1939. Fisrt series. V. III, 1919. London, 1949. p. 786-787.

Mackinder H. J. The geographical pivot of history The. Geographical Journal.1904.№ 23, С.421–437.

Mackinder H. J. The Nations of the Modern World: An Elementary Study in Geography and History. London: George Philip, 1924.

Mackinder H. J. The Round World and the Winning of the Peace//Foreign Affairs. 1943. Vol. 21& № 4 (July).

Mackinder H. J. The Scope and Methods of Geography and the Geographical Pivot of History. L., 1951.

Mackinder H. J. The world war and after: a concise narrative and some tentative ideas. London: G. Philip & Son, Ltd., 1924.

Mahan A.T. The Problem of Asia and Its Effect upon International Policies. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co., 1900.

Mahan A.T. The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1897.

Mahan A.T. Sea Power in Relation to the War of 1812. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1905.

Malraux A. La Tentation de l'Occident. Paris: Grasset, 1926.

Manifeste de la GRECE. Paris: Labyrinthe, 2001.

Mann St. R. Chaos Theory and Strategic Thought//Parameters. 1992. Autumn. № 55. Русский перевод: Манн С. Теория хаоса и стратегическое мышление. – www.geopolitika.ru. [Электронный ресурс] URL: http://geopolitica.ru/Articles/890/ (дата обращения 05.08.2010).

Markedonov S. Unrecognized Geopolitics // Russia in Global Affairs. № 1. January — March 2006.

Maull O. Das Wesen der Geopolitik. Leipzig: B.G. Taubner, 1941.

Maull O. Politische Géographie. Berlin: Gebrüder Borntraeger, 1925. Mauss M. Sociologie et anthropologie. P.:P.U.F.,1966.

McCain J. League of Democracies (op-ed)//Financial Times. 2008. March 19.

McFaul M. Advancing Democracy Abroad: Why We Should and How We Can. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009.

McFaul M. Russia's unfinished revolution: political change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002.

McFaul M. U.S.-Russia Relations in the Aftermath of the Georgia Crisis. Washington: U.S. House of Representatives, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, 2008.

Meyer J., Boli J., Thomas G., Ramirez F. World Society and the Nation-State// American Journal of Sociology. 1997.№ 103(1). С. 144-181.