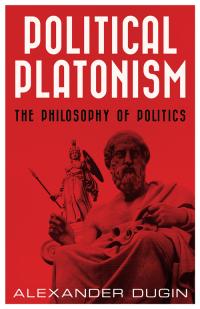

Radical Object: the necro-ontology of Dark Enlightenment (Negarestani's philosophy)

The Globalists might appear to be looking for some kind of increased living standards and opportunities for people in a world without borders, new destinies for migrants happily moving without documents to foreign territories, but this story, this narrative of the earlier, rosy Open Society and early liberalism is only for the news. The most foundational, responsible, and realistic thinkers of speculative realism have already arrived at a different agenda. Their commentaries, criteria, terms, and projects are much closer to this active demonic nihilism. Here we can recall Friedrich Georg Junger’s words that where there are no gods, there are titans. There is no void. Where there are no angels, there are beasts. If we close the world egg on the top, we open it from the bottom. If we refuse God, the Devil comes. Man doesn’t come, as man can only stand so much in place without God. It turns out that the one who nudged man to kill God was not man himself, not of his own will, but rather the one standing behind him who, according to skepticism and rationalism, isn’t supposed to exist. The Devil pushed man to assert that there is no God, that there is only the material world, and now he is saying: “Greetings, my dear, you have done what I requested. It is I, I am Reza Negarestani, I am object-oriented ontology, I am progress, I am the 3D printer, now I will print you and your offspring, and everything will be well.” Gradually, humanity will be “packaged” in the supermarket of dark enlightenment.