4pt

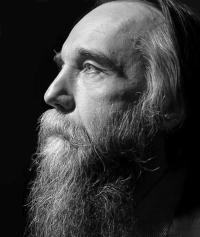

DUGINOVA SMERNICA

Týchto 14 bodov treba považovať za sémantické uzly suverénnej ideológie. Odteraz štát prevzal zodpovednosť za stav verejného vedomia a sociálny model, alternatíva Západu, bude vychádzať z nich. V istom zmysle sa stávajú posvätnými."

Prvé tri body sú spoločné pre ruskú tradíciu a liberálne ideológie Západu.

Právo na život . Prvý bod uznávajú rôzne spoločnosti – tradičné aj moderné – ako tradičnú hodnotu. Život človeka je zverený len jemu a iný človek nemá právo vziať život druhému podľa vlastného uváženia. Navyše v náboženských spoločnostiach sa za trestný čin považuje aj samotný akt samovraždy (nehovoriac o nátlaku k nej vedúcemu).

Jedinou výnimkou je štát, ktorý má za určitých okolností právo nakladať so životmi svojich občanov – trestať odsúdených za preukázané zločiny alebo ich posielať bojovať na obranu vlasti. Ale ak je život tradičnou hodnotou, ktorú treba zachovať a posilniť, potom by to mal štát brať do úvahy v extrémnych prípadoch – preukazovať, ak je to možné, milosrdenstvo voči zločincom a chrániť životy vojakov a bojovníkov.

RUSKÁ IDEOLÓGIA A CIVILIZÁCIA ANTIKRISTA

Dnes už takmer každý chápe, že bez ideológie ŠVO nemôžeme vyhrať. A čo to je za ideológiu, je tiež každému krištáľovo jasné. Toto je ruská myšlienka, ktorá zahŕňa sebavedomé a nekompromisné presadzovanie našej identity, našej etiky, spravodlivosť, vernosť odkazu predkov, nezávislosť a slobodu vlasti od tlakov, vplyvov a útokov. Táto ruská idea nám bola odopieraná najmenej 100 rokov. Teraz však bez nej nemôžeme urobiť jediný krok vpred a dokonca ani zachrániť to, čo máme. Bez ruskej idey sa jednoducho zrútime – nehovoriac o víťazstve vo vojne.

COUNTER-HEGEMONY IN THE THEORY OF THE MULTIPOLAR WORLD

Although the concept of hegemony in Critical Theory is based on Antonio Gramsci’s theory, it is necessary to distinguish this concept’s position on Gramscianism and neo-Gramscianism from how it is understood in the realist and neo-realist schools of IR.

The classical realists use the term “hegemony” in a relative sense and understand it as the “actual and substantial superiority of the potential power of any state over the potential of another one, often neighboring countries.” Hegemony might be understood as a regional phenomenon, as the determination of whether one or another political entity is considered a “hegemon” depends on scale. Thucydides introduced the term itself when he spoke of Athens and Sparta as the hegemons of the Peloponnesian War, and classical realism employs this term in the same way to this day. Such an understanding of hegemony can be described as “strategic” or “relative.”

In neo-realism, “hegemony” is understood in a global (structural) context. The main difference from classical realism lies in that “hegemony” cannot be regarded as a regional phenomenon. It is always a global one. The neorealism of K. Waltz, for example, insists that the balance of two hegemons (in a bipolar world) is the optimal structure of power balance on a world scale[ii]. R. Gilpin believes that hegemony can be combined only with unipolarity, i.e., it is possible for only a single hegemon to exist, this function today being played by the USA.

In both cases, the realists comprehend hegemony as a means of potential correlation between the potentials of different state powers.

Gramsci's understanding of hegemony is completely different and finds itself in a completely opposite theoretical field. To avoid the misuse of this term in IR, and especially in the TMW, it is necessary to pay attention to Gramsci’s political theory, the context of which is regarded as a major priority in Critical Theory and TMW. Moreover, such an analysis will allows us to more clearly see the conceptual gap between Critical Theory and TMW.